“Education through video games is no longer just an optional extra; it has to be done!”

39 million.

This is the number of video game players in France - over 50% of the national population. A study published in October 2023 by the SEII (French association of leisure software publishers), “The French and video games” challenges the most persistent prejudices. The average age of players is 40; almost half of regular players (at least once a week) are women; more than 7 out of 10 French men and women say they play occasionally (at least once a year). In other words, the phenomenon is massive. And France is far from an isolated case. With more than 237 million video game players, the figures are similar throughout the European Union.

And yet, video games are still not taken seriously. An object of fantasy for some, of disinterest for others, video games are largely unknown to many. Few people have the tools to critically analyse video game productions. And with good reason: the development of these tools is still in its infancy! William Brou is well acquainted with this task of organisation and raising awareness, as he contributes to it on a daily basis.

We speak to the former history and geography teacher and creator of the YouTube channel Histoire en Jeux. Since 2018, he has been in charge of the “Gamification, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR)” project at the Clermont-Ferrand Education Authority.

_____

First of all, what do we mean by “video games”? What are the educational opportunities you have identified?

William Brou: Video games are the number one cultural medium in the world. They generate billions and billions in sales. Education through video games is no longer just an optional extra, it has to be done! Particularly with schoolchildren, for whom games are a part of everyday life. Parents don’t always have the time or the skills to do this. Schools need to help children develop a critical eye; we need to jointly educate them about these artistic, cultural and industrial objects.

As part of my work at the Education Authority, I help colleagues to incorporate video games into their lessons. I recommend letting students play as normally as possible, as they would outside school. In other words, with games they know and think they’ve mastered, but also by raising the stakes. It’s all about having fun, and it has to stay that way. Otherwise, the gaming is biased and the learning outcome is not the same. The aim is for the student to become aware of the different components of the game, the language used, the way the story is told, and for them to make the link with their own gaming in order to develop reflexivity and avoid being manipulated without realising it. It also changes the context of the classroom and creates a different teacher-student dynamic.

In practical terms, how do you incorporate a game into a lesson? It doesn’t seem very compatible with the constraints of school work. Can you give some examples?

In fact, it’s incredibly simple. Let’s take the example of the subject I know best: history. Each year, we have a certain number of concepts and subjects to look at with the students. These concepts can be approached in many different ways. Take the First World War. We can organise a school trip to Verdun, the site of the deadliest battle of the conflict. We can prepare a screening of Christian Carion’s film Joyeux Noël. We can use archives and historical documents. Students can be asked to give presentations. Or give a lecture. We have the pedagogical freedom to choose the angle and the method. So why not use a video game? There are plenty of video games dealing with the First World War.

All you need is some equipment: at least one console and the game. There is no need for every student to have their own console and game. On the contrary: this would mean that they were playing alone in front of their screens. Playing in front of spectators poses no problem. Students are used to this type of practice. And it has an educational benefit. The students who aren’t playing are going to react. They will notice things that the player does not see: the background, small details. These reactions are part of the gaming experience. It makes the game more collaborative and the experience more convivial. We mustn’t neglect this notion of fun. You have to allow for play, especially with difficult classes. It’s important to remember that school can also be enjoyable.

If we take the First World War as an example, a few years ago I put together a lesson based on Battlefield 1. My starting point was: “We have a problem. All documents relating to the First World War have disappeared. All that is left is this game. What does it tell us about the conflict?” We explore the game, and together we describe how the First World War is represented in it. Then comes the critical analysis: what do you think? Does it seem credible? Is there anything that strikes you as odd? This leads students to ask themselves questions: “But sir, why is this in the game?” It opens up new avenues of research, which I add to with historical documents. We really look at knowledge in a different way: knowledge becomes useful in the context of the course. The documents regain their rightful place as traces of the past and allow for a real critical study of video games: “This aspect of the game is credible because in this document, we have testimonies from doctors who talk about the traumas linked to the brutality of war.” It gets students to take a deductive approach, which encourages them to become active learners.

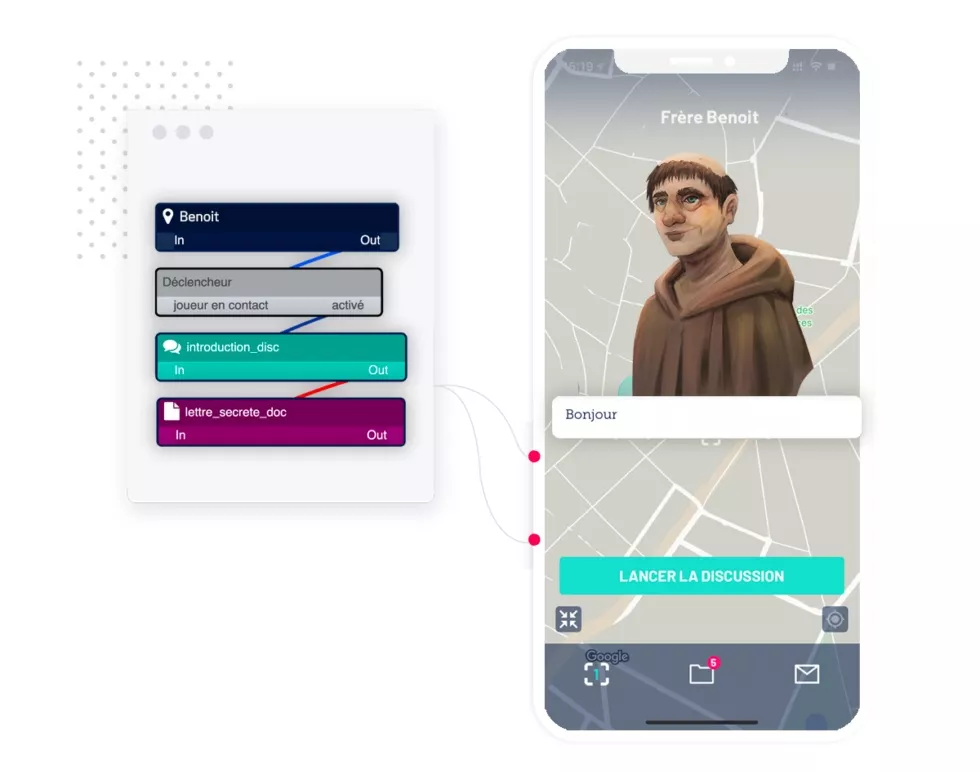

I like to get the students to create games too. It opens up a whole host of questions: what characters are we going to include? What can they tell us? What type of information will be provided? A rumour, an anecdote? The students will have to ask themselves all these questions to create their game, which means that they will have to do some documentation work beforehand.

And the skills they develop go well beyond the scope of the lesson!

Technically, making a video game calls on all the skills required by the common foundations: writing an argumentative text, completing or creating a map, filling in a table, creating a graph, etc. When you use a game, you have to keep in mind the skills you want to work on. You can’t do everything in one lesson with your students. To critically analyse an entire game, or create one from scratch, would take a whole year. If I want to work on writing, I can focus on writing dialogue, for example. Which is a great start! Producing an interactive game with extensive dialogues requires students to think about narrative choices, to imagine several plausible endings. It’s not that easy.

However, using video games for education also means talking about guidance issues. For a long time, games were seen as something created by geeks. You just have to be a good coder and that’s it, you can make a game. When we analyse AAA or AAAA games (games with very large budgets), such as Assassin’s Creed, we realise just how complex these productions are. We have game designers who come up with the rules of the game, and programmers who create the rules in the game engine. Then there are the level designers who create the game map, and the artists who draw the objects that make up this world (trees, buildings, etc.). For the characters, there are character designers. For the dialogue, authors or scriptwriters are used. Breaking down the game in front of the students shows the diverse range of the professions behind it. They can project themselves.

The final word?

I would like to share an anecdote. When we do game creation workshops, we always wonder how to organise the students’ work: do we ask them to do everything together or divide up the different jobs? One year, with a colleague, we got students to create a geolocated treasure hunt about George Sand in Thiers. One of the teams spontaneously organised itself according to roles: a student who wasn’t very academic chose to draw all the characters in the game. Initially, she had wanted to take a back seat. In the end, she was the one who asked the most pertinent questions: what should George Sand’s face look like at the end of the game? Does she have emotions? Should there be one face or more? This forced the team to work on the narrative more carefully. At the beginning, the character is sad because a book has been stolen from her. But in the end, if the quest is successful, she should be happy. So at least two different faces were needed. But there was a technical issue: in the proposed game engine, one character = one image; there can’t be two faces for the same character. The team ended up calling the game’s developer. Together, they came up with a trick: add a final discussion with George Sand, with two possible answer choices. One will produce a sad George Sand face, the other a happy one. This is transparent to the player, who can’t see the difference. But in the game engine, it’s quite complex. It was a real collective journey. Today, this student is studying at art school, and specialising in video game animation.

[Translation : NSS EPALE France]

Comments

Fully agree with this point…

Fully agree with this point of view!