Ecological crisis: the value of educating about the Anthropocene (“the human epoch”)

We are now living in the “human epoch”. This is the main notion that the concept of the Anthropocene (Anthropos for “human” and cene for “new”) seeks to convey. The approach is not about navel-gazing; rather, it points to the terrifying and unprecedented impact of human activities on our environment. At a time when climate and health crises are ramping up and awareness of the threats that humanity itself has created is growing, the Anthropocene could play a fundamental role in education and in the radical changes required to reduce these threats, both for learners - who need to play an active role in the transitions - and for educators - who need training on ecological issues and the associated pedagogical challenges.

Raising awareness of human power and responsibility towards the living world

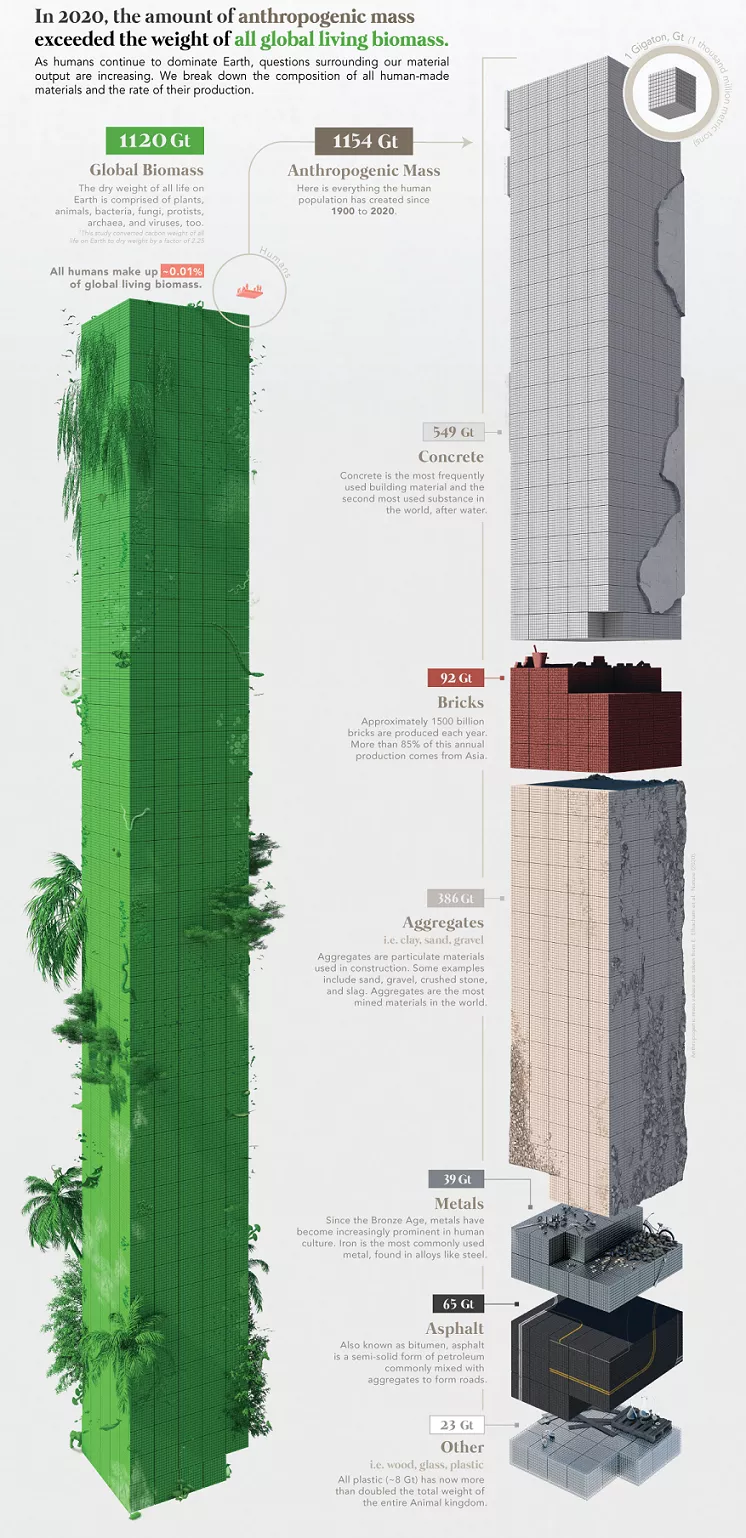

The Anthropocene points to the impacts of human activities, which have become so far-reaching that humanity as a whole could almost be considered a geological force in its own right.

- Some of the planet's limits are close to being reached or have even been exceeded, such as the nitrogen cycle and biodiversity loss. Humans have amplified their impact through population growth and the use of techniques that increase the potential of each individual, from agriculture to digital objects, the use of heat engines and chemicals.

- Although not all humans have contributed to this situation to the same extent, they are all exposed to it in one way or another: air and water pollution, habitat destruction, pandemics, global warming, depletion of resources, etc.

- The risks associated with the use of human power are now major and give humanity a glimpse of the benefit/risk balance of technological and political choices, which is now explicitly tilted towards a danger for ecosystems, including humans.

Beyond the term, which may understandably repel some learners, it is above all a question of using fundamental components to enable in-depth analysis of an ecological crisis, the complexity of which is becoming more and more visible every day. This step helps us to realise that “the consequences of the Anthropocene are the result of past political developments, that they are not all inevitable and that its trajectory is not either”.[1]

Understanding the systemic nature of socio-ecological issues

Balances have been upset and the consequences for the environment are countless: disruption of the balance of current living conditions, particularly climatic and biogeochemical conditions, disappearance or degradation of the habitats of many species and populations, increasingly rapid growth in human construction and pollution, destruction of landscapes, etc., which are the flip side of a coin that has also brought “progress” to a significant part of the world's population: increasing population and life expectancy, increasingly comfortable and consumer-oriented lifestyles, international tourism, previously unthinkable transport and communication possibilities, etc. It is difficult to comprehend, as there are so many entanglements. Studying them allows us to better elucidate the relationships between the various phenomena. Thus:

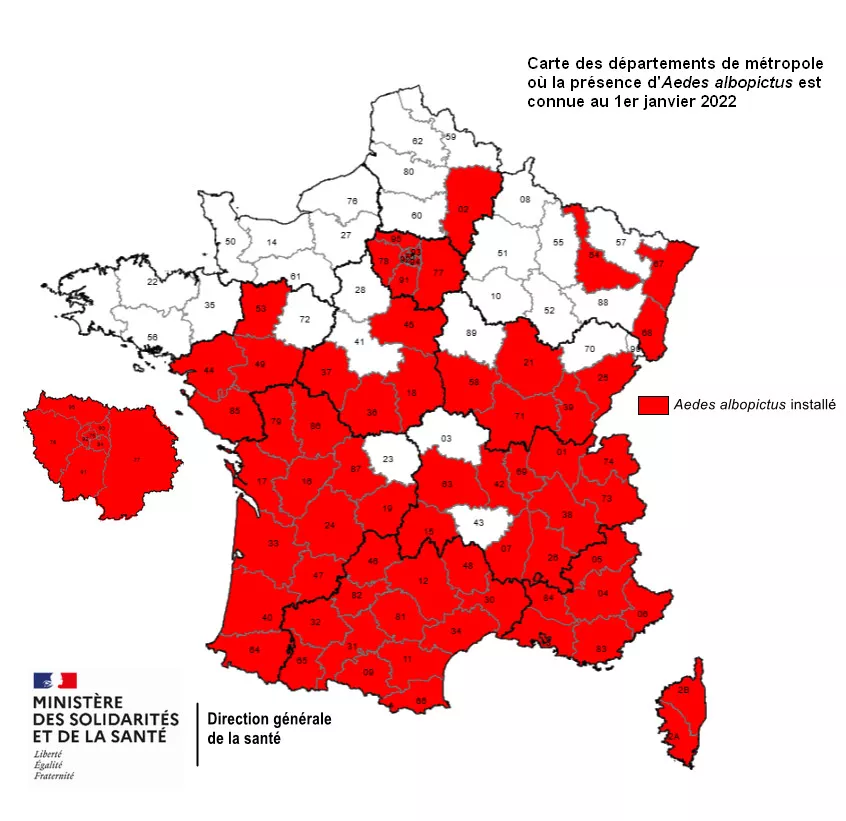

- Climate change is both the consequence of the systemic use of fossil fuels (oil, coal, gas) by our societies, and the source of a chain of consequences in all strata of our lives and those of our animal and plant companions: it is not only a question of an increase in air temperature, but also of a disruption of a climate whose relative stability over the last few thousand years has enabled the emergence of our societies. Heat waves are already increasing in intensity and frequency, having a lasting impact on our soils and therefore on our food crops and infrastructure; extreme weather conditions are and will be more intense and frequent; animal, plant and human populations have already begun to migrate to find less hostile lands. How could the French have imagined, 10 years ago, that the presence of the tiger mosquito, a potential vector of dengue fever and chikungunya, would become a reality in 67 French departments by 2021?

- To become such a prominent power on the face of the Earth, humans have transformed their environment: they have cut, dug, burned, buried, watered, transported, crushed, assembled, built, destroyed, and played with the elements. And since all physical transformation involves the use of energy, the availability and ease of use of energy is crucial. After water, wind and wood: coal. Then oil, in addition to, not in place of, gas, nuclear fission, etc. The various machines we have created have enabled us to use these energies to achieve our ends (and hopefully not to bring about end of us all): mills, boilers, engines, dishwashers, chick crushers and smartphones are among them.

- The use of phenomenal quantities of energy, with no real limitation other than the possibility given to everyone to use it (industry, the government, individuals) has created many victims, more or less directly[2]. Territories, species and people have undergone direct devastation or have even been wiped out. Some have been deprived of ancestral landscapes of fundamental spiritual importance; others have been colonised. Journalists and activists are harassed or even murdered. Let's not forget those who are invisible and resource-less, who have no way of calling out the grabbing or destruction of which they are victims, as well as the attacks on their health and their rights.

Understanding the links between the components of the Anthropocene allows us to better envisage the most desirable outcomes. Investing in the Anthropocene allows us to think better, before charging ahead.

Developing cross-disciplinary learning

Faced with the systemic nature of socio-ecological crises, singular disciplinary responses cannot suffice. Developing cross-disciplinarity in education is therefore essential. The Anthropocene can play the role of a vertical and horizontal ladder allowing educators and learners to associate physical and biological issues with human and social issues. This would enable the development of popularisation skills, particularly scientific outreach, which is necessary for cross-disciplinary action.

- Attempting to place a date on the beginning of the Anthropocene is a good excuse for debate including historical, geographical, physico-chemical, political and cultural elements. Some will focus their thoughts on technological advances that are significant for our modern societies (and most often related to energy!): the invention of the steam engine or the heat engine, or nuclear explosions. But others will see it only as a tool of liberal economic doctrine and its narrative of progress. The concept of the Anthropocene may be challenged and some may suggest calling this era the “Capitalocene” or “Thermocene”. Some will go back to the Neolithic period and the beginnings of agriculture, when humans began to actively modify their environment and probably already increased the levels of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere.

- Teaching about the Anthropocene is a way of beginning to respond to the younger generation, some of whom are disenchanted with the celebrated progress of the twentieth century, eco-anxious[3] and furious about their jeopardised future. Many educators are at a loss when faced with the need to teach new, complex and sometimes (at least apparently) very different issues from their original teaching. Initiatives are flourishing to try to meet these needs: a 12-hour MOOC on “Education on the Anthropocene” by the University of Paris[4], a 10-hour course on “The Anthropocene and the climate” for first-year students at the INSA in Lyon, etc.

Drawing on the natural sciences, the humanities and social sciences

Cross-disciplinarity implies being able to draw on the contributions of many disciplines and realising the complementary nature of the natural sciences, the humanities and social sciences for this purpose.

- The “great acceleration”, studied by pioneers of the Anthropocene (meteorologist and atmospheric chemist Paul Josef Crutzen, environmental scientist Will Steffen and historian John McNeill), links indicators of socio-economic trends with those of the Earth system. The indicators of degradation of the Earth system, such as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, surface temperature, ocean acidification or deforestation in tropical zones, are (generally) increasing exponentially, and are correlated with a vertiginous acceleration of socio-economic indicators: human population, global real GDP, urban population rate, primary energy use, fertiliser consumption, telecommunications, etc. The links between GDP, energy use, climate change and destruction can thus be analysed. This research, supported by different types of indicators, shows the importance of moving away from a solely climate science or biology-based vision. And how can we understand the scenarios of responses to these challenges without talking about economics, psychology and politics?

- Conversely, misunderstanding the physical and biological nature of humans and the living world in general could lead us to believe that we can negotiate with nature, which is not the case. The natural sciences also demonstrate the urgency to act in response to these accelerations (as evidenced by the IPCC reports on climate change), and allow us to better define our collective priorities.

Overcoming the technically oriented view of the socio-ecological crisis in education

The Anthropocene crisis requires more than a technical, social and political response. Because of its origins, which are certainly buried deep in our minds and tribes, in our hearts and bodies, it can be taken up by education and training as an opportunity, almost an excuse, to place more importance on certain issues which are sometimes relegated to the background.

- As an educator or trainer, it allows you to question your role. Should I deal with the ecological crisis, the Anthropocene, pollution and environmental public policy in my teaching? What angle should I choose, how deeply should I approach these subjects, how should I take into account the level of knowledge or eco-anxiety of my audience?

- It therefore invites us to broaden the ecological crisis to horizons that are sometimes far removed from the usual prisms of analysis: philosophy and moral questions, ancestral knowledge, spirituality, citizenship. What is the role of humans in this world?

- Those involved in education can also question top-down pedagogical practices in the face of constantly evolving, complex knowledge with major social, political and democratic stakes.

Conclusion

The concept of the Anthropocene allows us to analyse the ecological crisis with a systemic approach and without reducing it to a purely physical or technical issue. It establishes the links between socio-economic development and the impacts of this “progress” on ecosystems and on the Earth system to which we belong. It thus raises the question of the past and, above all, the future trajectory: what individual, entrepreneurial, social and political choices do we want to make, with the awareness that these choices are intertwined with the future of the current Anthropocene?

In the field of education, the study of the concept makes it possible to go beyond education for sustainable development and to deeply question human trajectories and their consequences “elsewhere”, without necessarily considering the near future as a philosophical or political continuity of the dominant societies of the last two centuries, based on an idea of the superiority of humans over the rest of nature and on infinite growth in a finite world. The concept also highlights the importance of cross-disciplinarity and participatory teaching practices.

[1] Steffen, Will et al., « The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration », The Anthropocene Review, mars 2015.

[2] Garnier, Alix et al., « Éduquer en Anthropocène:un paradigme éducatif à construire pour le 21ème siècle », Recherches & éducations, no. 23, novembre 2021.

[3] {Effrayée par les crises actuelles et promises à empirement, et abattue par le manque de prise sur les changements nécessaires}

[4] « L’éducation en anthropocène », FUN MOOC, [s. d.], <http://www.fun-mooc.fr/fr/cours/leducation-en-anthropocene/>

Images :

DGS_Céline.M et DGS_Céline.M, « Cartes de présence du moustique tigre (Aedes albopictus) en France métropolitaine », Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention, 24 octobre 2022, <https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/sante-et-environnement/risques-microb…;

Venditti, Bruno, « Visualizing the Accumulation of Human-Made Mass on Earth », Visual Capitalist, 29 novembre 2021, <https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-the-accumulation-of-human-…;