Career readiness and “green” career choices

Author: Anthony Mann

Over recent years, the OECD has explored teenage attitudes towards climate change and other environmental concerns from a number of perspectives. In this article, I highlight findings from three studies which draw on statistical data to help build understanding of student attitudes and approaches to career guidance that can be expected to enhance understanding and ameliorate pathways into sustainable employment.

© Chayantorn Tongmorn/Shutterstock.com

Insights from PISA on student perspectives on green futures (OECD countries)

Every three years, 15 year old students in dozens of countries around the world (both OECD member countries and others) complete a series of questionnaires testing their proficiency in mathematics, reading and science and gathering a wide range of information about their attitudes and experiences. In addition, in this PISA study (www.oecd.org/pisa) data are collected about the schools they attend and their social backgrounds. This unique dataset tells us much about the lives of young people as they move towards the end of their secondary schooling. The latest PISA results relate to questionnaires completed in 2018 when 600 000 students from 79 countries and economic areas took part.

The green generation: What 15 year olds have to say about the environment

See: OECD (2020), PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI): Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World?, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d5f68679-en.

Firstly, there are many positive results. Overwhelmingly, students say that school is the place where they expect to learn about the environment and nine school principals out of ten say that global warming or climate change is covered in the curriculum. Most students (72%) say they are confident that they can explain why some countries suffer more from global climate change than others. Many (65%) say they could discuss the consequences of economic development for the environment or explain how carbon dioxide emissions affect global change (63%).

Around the world moreover, eight out of ten students across the OECD agree or strongly agree that "looking after the global environment is important to me personally." Many students actually take part in activities to try and support environmental protection. They say they try and reduce the energy they use at home (71%) and that they choose certain products for ethical or environmental reasons (45%). What’s more, students also are in favour of activism to actually support improvements in climate change. Many students say that they:

- take part in activities in favour of environmental protection (39%),

- boycott products or companies for political, ethical or environmental reasons (27%), and

- sign environmental or social petitions online (25%).

However, PISA finds that students with poorer knowledge and skills around environmental science often report an almost naïve optimism that the environmental challenges will simply go away in the future. Better knowledge enables students to realistically assess the magnitude of the challenges that lie ahead. Many students also feel powerless to effect positive change in the world. Only six out of ten (on average across OECD countries) agree that “I can do something about the problems of the world.” In Austria for example, some two-thirds of students agree or strongly agree that looking after the global environment is important to them personally, but fewer than half agree that they can do something themselves to address global challenges.

Do young people aspire to ‘green’ careers?

See: Mann, A and Besa, F, Looking for green engineers – Insights from PISA 2018, OECD Education Today Blog, March 22 2021.

So given the strength of young people’s concern about the environment, do we see them aspiring to ‘green’ careers? In PISA 2018, students were asked what kind of job they expected to do at age 30. Typically, across OECD countries around half of boys and girls at fifteen naming an expected occupation select one of just 10 professions. This level of concentration has been growing since the start of the century and in some countries, particularly outside of the OECD, now exceeds 70%. Among the most popular expectations – and it should be stressed these are the expectations of students, not their hopes – are professions like doctor, teacher, lawyer and police officer. In the PISA assessments, students write in their occupational expectation and it is then coded using the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) which was last updated in 2008. At first glance, it is difficult to identify interest in green careers. As the International Labor Organisation explains:

“Few occupations defined in the ISCO classification system are specifically associated with improving sustainability. Environmental professionals and refuse sorters are about the only … classifications that are specifically green, and even jobs in refuse sorting will not be green where the work produces damaging emissions or waste, or where it fails to comply with standards for decent work. Most green jobs are in occupations that also cover non-green jobs. For example, a mechanical engineering technician working in renewable energy or waste processing may be regarded as being in a green job, while a mechanical engineering technician with broadly similar skills working in manufacturing or a fossil-based energy industry is not, unless the job is focused primarily on process improvement.” (Gregg, C. et al. 2018, Anticipating skill needs for green jobs A practical guide, ILO)

However, it is possible to drill down into interest in engineering. The challenge of climate change demands a new generation of engineers to enhance sustainability across a wide range of areas – manufacturing, transportation, construction, energy production – all requiring skilled engineers.

On average across the OECD, 7.8% of boys and 1.8% of girls at age 15 with an occupational expectation say that they will be an engineer by the age of 30. This gender gap is important and deserves attention, but it is not the subject of this paper. Rather, our investigation has focused on whether students who feel more passionately about the environment are more or less likely to express an interest in a career in engineering than their peers who do not. Is engineering seen as a ‘green’ career? Does it attract greatest interest from those who are most concerned by climate change? The answer to both questions is no. Across OECD countries, 4.4% of all 15-year-olds who agreed strongly that that looking after the global environment was important to them personally anticipate working as an engineer by age 30, compared to 4.3% of students who are less concerned by green issues.

Effective career guidance: the OECD Career Readiness study

See: www.oecd.org/education/career-readiness

This result can be understood from two perspectives. On the one hand, it may well be that in many countries, engineering can still not be reasonably be considered as a green profession, that manufacturing, transportation, construction and so on are failing to adapt to the existential challenge of climate change. From another perspective, it may be that the profession has adapted or is in the process of adapting, but that adaptation is not being understood by young people, that the labour market is not yet signaling effectively to young people.

While the guidance community cannot be expected to change the engineering profession, it does have a responsibility to ensure that young people understand its contemporary character. There is good reason to believe however, that many students go through their education with a poor understanding of the world of work in all its guises. The PISA2018 survey for example finds that only 50% of students have (on average across participating OECD countries) spoken to a career advisor in school by the age of 15 and that fewer than 40% have participated in a job fair, attended a workplace visit or undertaken an internship. One in four students is unable to name the kind of job that they will do by the age of 30 and one in five (rising to one in three of the most disadvantaged) aspire to a career typically requiring university level education but do not plan on continuing to higher education.

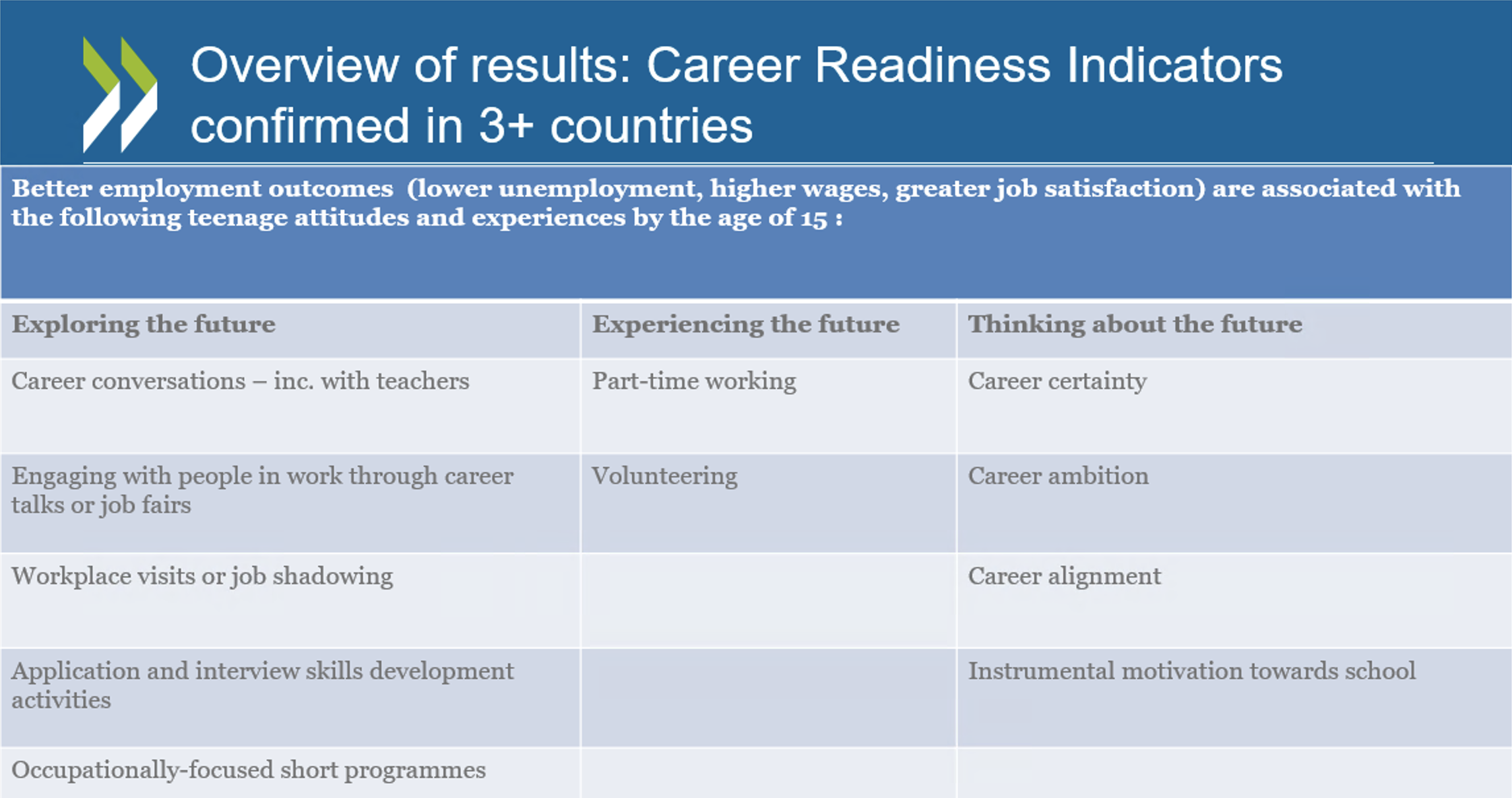

Over the last year, the OECD Career Readiness team has undertaken an unprecedented review of the datasets investigating the link between teenage career-related attitudes and experiences and employment outcomes in adulthood. The study focuses on longitudinal datasets in 10 countries (Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Germany, Korea, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States and Uruguay). Such datasets follow large representative samples of children through their teenage years into adulthood. By using statistical controls for those aspects of lives that commonly shape labour market outcomes (gender, social background, academic achievement, geographic location etc.), it is possible to identify which aspects of teenage lives around age 15 can be associated with lower unemployment, higher wages and greater job or career satisfaction around age 25. For the first time, a multi-country review on this scale has sought to identify such indicators of teenage career readiness. The study concluded by confirming 11 such predictors.

Confirmed indicators of teenage career readiness

A first insight to highlight from the results is how strongly first-hand engagement with the work of work features within the indicators. Students attending career talks or job fairs, visiting workplaces or undertaking job shadowing can be expected to do better later on, as can students who participate in activities to develop their applicate and interview skills – provision that is often delivered with employers. Participation in occupationally-focused short programmes that are especially popular in Australia, Canada and the United States also typically involve employer engagement whether through work placements, curriculum enrichment or career guidance. Such courses typically last a day or two a week and take place within general education. Finally, first-hand experiences of work through part-time employment or volunteering can be consistently related to better outcomes. It is worth noting here that some evidence also exists that school-managed work placements can also be beneficial, but the data is too limited to confirm the activity as an indicator. Effective programmes therefore should focus on giving students plentiful opportunity to engage directly with people in work and to see workplaces for themselves. It is their opportunity to gain information that is new and useful because it broadens and personalises career thinking through interactions that are difficult to ignore because they are more likely to be perceived as authentic.

Through such exploration, it is possible to see young people becoming more mature in their career thinking – a second important insight. Plentiful evidence is found in the PISA2018 dataset that students who take part in guidance activities can expect to be clearer, more ambitious and more aligned in their career planning. They are more likely moreover to see a positive relationship between what they do in the classroom and who they may become professionally in adulthood.

This statistical relationship underpins the importance of schools encouraging and enabling a culture of curiosity and exploration among their students. One of the most striking indicators relates to career conversations with career advisors, teachers, family members and friends of the student. It may be difficult to imagine a student gaining insights of such value in a single conversation as to enhance career outcomes ten years later, but this is what the data show. It can perhaps best be understood in terms of what it says about the attitude or disposition of the student. A young person who is engaging in conversations with people around them is showing an important degree of engagement. They are actively seeking to visualize and plan a future for themselves. Such engagement cannot be left to the end of lower secondary education or other such high stakes decision-making points. Effective guidance will be, as Australia scholar Jim Bright argues, early, often and integrated into educational provision. It will also be rich in multiple opportunities to engage with people in work and workplaces that will broaden, raise and challenge emerging thinking and provide young people with information and experiences that will underpin the personal agency increasingly expected of them as they navigate their choices through education and training. Effective guidance begins in primary school, helping young people to build their understanding of the links between education and employment and to challenge stereotypical thinking about what is ‘right’ by way of vocation for any individual to pursue.

What are the implications of the OECD career readiness study for supporting the development of green guidance?

The OECD’s analysis shows that routinely labour markets are not signaling well to young people. The career ambitions of 15 year olds have little changed since 2000 when PISA first asked them about the jobs they expected to be doing at age 15. It cannot be taken for granted that students will understand the breadth of the contemporary world of work, the trends within it or the relationships between educational provision and employment outcomes. This can be expected to be a particular challenge during periods of labour market disruption as is currently being experienced due to digitalization/automation and the Covid-19 pandemic. A green future depends upon green skills. The ILO anticipates millions of new green jobs emerging over coming decades. Recruitment planning requires effective signaling to young people about such careers. The OECD Career Readiness study highlights the essential importance of ensuring that students are given plentiful opportunity to understand these emerging occupations and pathways into them. Here, it is the task of governments to ensure that it is easy for schools and employers alike to connect. In many countries, intermediaries fulfil this role. Some like, Inspiring the Future in the UK harness online technologies to reduce the costs and increase the effectiveness of connecting the right professionals with the right students at the right time. Where it is quick, easy and free for both sides to engage, such innovations have an important place in the strategic toolkit of administrations responding to the deep challenges of climate change.

Colleagues may also be interested to see the ways in which education systems are responding to climate change within subject pedagogy with key global statistics on the challenge at hand to secure an environmentally sustainable future.

OECD (2022), Trends Shaping Education 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6ae8771a-en.

Finally, during 2022 the OECD plans to continue its work on Career Readiness, including new analysis on how schools can best support the progression of young people towards green employment. To join our mailing list for free monthly updates on the work which will also focus on guidance to address social inequalities and the use of digital technologies in guidance, please email career.readiness@oecd.org.

About the author

Dr. Anthony Mann, Senior Policy Advisor for Vocational Education and Adult Learning, is head of the team for Vocational Education and Training and Adult Learning at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris. Over the last decade, Anthony’s team has undertaken more than 50 country reviews and produced numerous thematic studies, most recently on work-based learning.

This text is based on a lecture at the Austrian Euroguidance Conference "Green Guidance" in November 2021.

Comments

sustainability

Green career choices are important but even more so to ensure that all jobs contribute to sustainability. This is the real change necessary.

Such an article gives us so…

Such an article gives us so much to mull over. We need to make sure that the positive indications are fostered and promoted, especially via the educational systems.

social enterprise

I think it is also important to consider the roles of social enterprises within such a discourse.