Life skills for adults

Author: Estera Možina, head of thematic field at the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education

“Life is the ultimate curriculum!”

(After T. Ireland, ICAE Workshop at the World Social Forum 2021 on why is Freirean´s pedagogy important nowadays.)

Introduction

Life skills have been in the focus of adult education policies and practice in Europe in recent years. Although there are already many different definitions and applications of the term ‘life skills’ in practice, one hardly argues which view or definition is right or wrong. In general, in adult education practice the term has been quickly accepted. The situation is somewhat similar with the term ‘functional literacy’, which most people easily understand and apply to their concrete situations in contrast for example to terms like ‘key competences’ or solely ‘literacy’ and/or ‘numeracy’. Nevertheless, there have been several attempts to define the content and the scope of the term as well as the theoretical underpinning and origin of the term. Among them, there are the endeavours of the partnership implementing the two-year Life Skills for Europe (LSE) project that was completed in 2018. LSE was one of the first international projects that strived to systemise existing definitions and approaches to life skills in adult education in Europe (Javrh et al, 2018) and develop a life skills learning framework for adults. The LSE project was proposed and coordinated by EAEA, the organisation that advocates for the role of non-formal adult education for social inclusion in the EU. This article summarises the understanding of life skills mainly as it is perceived within the LSE project.

Life skills in the focus of adult education policy and practice

Life skills are not only the focus of adult education policies and practices on a national level. The European Skills Agenda also emphasises the role of non-formal adult education for the benefit of individuals, the society and the economy (EC, 2020). Action 8 specifically points out ‘Skills for Life’. In addition, life skills are supported by the European Pillar of Social Rights stressing lifelong learning as a right (EC, 2017). The result is a EU headline target stating that at least 60 per cent of adults should participate in training every year by 2030 (EC, 2021). The life skills approach is also in the scope of endeavours of adult education associations in the EU such as the European basic skills network (EBSN), which has been supporting the development of integrated policies and measures, as well as holistic approaches and programmes for the development of basic skills of adults in the EU.

The rationale for the focus of adult education policies on life skills is the present state of the art as regards the level of skills and participation in lifelong learning by certain groups of adults in most Member States. To mention only a few aspects:

- millions of adults with low skill levels in the EU or with insufficient skills for lifelong learning, life and work (one in four adults aged 16 to 65 in the EU has a low level of literacy and/or numeracy skills [OECD, 2019]),

- evidence that the level of education and age are factors determining participation in lifelong learning, adults with low education levels participate from 1.6 to 12.1 times less frequently compare to adults with tertiary education (labour force survey data series 2011–2020),

- a growing number of migrants and refugees in the EU who need to develop skills and competences in order to live in the EU,

- insufficiently effective programmes for the development of skills and competences that will enable long-term effects for the most vulnerable groups on a larger scale,

- evidence that the cost of the gap in skills for societies and economies is higher than the necessary investments in skills,

- evidence that better skills lead to individual and societal benefits (better health, higher trust of others, better wages, high participation in voluntary activities, high political efficacy [OECD, 2019]).

The question is why educational policies do not reach the most vulnerable adults. And also, what can life-skills approaches offer in this respect?

Why life skills?

Life skills are closely related to the key challenges adults are faced with in the modern world. They are intertwined with the particular situations throughout life because they are the result of a constructive processing of information, experiences, and more as part of one’s daily life and work. The social dimensions are particularly important as they compel individuals to acquire skills and intentionally develop attitudes and values in order to face and master real-life situations. And finally, activities over the course of life take place in a variety of contexts (political process, workplace, at home, in the community or in non-formal and informal settings), sectors and domains (health, environment, gender, work etc.) of human existence. Therefore, in the context of different life situations, life skills need to be adapted and defined.

It is inevitable that there are a plethora of different views and understanding of what life skills are. The constituents of generally defined life skills may include skills and abilities necessary to apply conceptual thinking and reflection in concrete situations; capacities for effective interaction with the environment and motivation to learn; as well as psychological prerequisites for successful performance (problem solving capacities, self-confidence and skills for critical thinking). In practice, definitions or even frameworks for life skills may focus on all three or just one of those aspects, most often psychological prerequisites for successful performance.

There are also a life-wide and life-long perspectives of life skills. Life skills are not limited to a specific age or stage in life. Lifelong or in this case ‘life skills learning’ is reflected in the knowledge, experience, wisdom, harmony and self-realisation rooted in the practical affairs of ordinary men and women (and not only in the national curriculum). They can also imply success in personal and professional life. From a social point of view they can mean cohesion, happiness, well-being and the good functioning of a group.

Influential authors and their concepts

A literature review reveals several influential authors and their thoughts that are very relevant for understanding life skills learning. For example Elinor Ostrom, an American economist (Nobel Prize laureate) gave us insight on involving people in governing the commons (Ostrom, 1990). Paolo Freire, a Brazilian adult educator, advocated for the development of skills of reflection that enables adults to take social action to improve conditions for themselves and their communities (Freire, 1970). Knud Illeris, a Danish professor of lifelong learning, pointed out the transformative role of learning and its influence on shaping one’s identity (Illeris, 2014). Specifically, the use of capabilities was drawn from the ideas of the Indian welfare economist Amartya Sen (also a Nobel laureate) and the American philosopher Marta Nussbaum. Sen has a lifelong preoccupation with inequality on a global scale, and with how we can use our individual and collective potential. His central idea is that we should pay attention to the development of human potential or capacity to achieve well-being. Sen advocated and developed his ideas on Martha Nussbaum’s analysis of gender issues in development that flows from the ‘capabilities’ approach to the analysis of quality of life. Nussbaum and Sen attempted to define well-being in an objective way, by identifying a set of core human capabilities that are critical to full human functioning and assessing well-being (and the success of development policies) by the degree to which the individual is in circumstances which lead to the realisation of these capabilities (Nussbaum and Sen eds., 1993).

Many aspects of the above-mentioned thoughts and theoretical backgrounds have already been shaping the existing definitions and/or frameworks for life skills education including the one proposed by the LSE project. For example the Unicef definition of life skills, which is part of a comprehensive life skills framework that promotes a holistic approach to education. According to Unicef, ‘life skills are a set of universally applicable and contextual abilities, attitudes and socio-emotional competencies that enable individuals to learn, make informed decisions and exercise rights to lead a healthy and productive life and subsequently become agents of change’. Furthermore, it is stated that life skills are a complement to and not a substitute for foundational skills like reading and mathematics and the two must be integrated rather than focused upon in isolation or parallel (Unicef, 2019, p.7 and 23).

Life skills for Europe – definition and learning framework

The interpretation of the taxonomy and the relations among terms such as skills, knowledge, competences, capabilities etc. is one of the authentic contribution of the LSE project. The insights into literature and existing practices within the LSE projects enabled the following definition of life skills: ‘Life skills are a constituent part of capabilities for life and work in a particular social, cultural and environmental context’ (Javrh et al, 2018, p. 4). The definition is simple and applicable in adult education. It does not imply a definite set of skills or capabilities, rather is open to amendments and combinations of skills. Life skills are sets of skills and capabilities that can lead to ‘an adult who is capable’, for example of social and civic engagement, self-efficacy, employability and critical thinking. The types of life skills emerge as a response to the needs of the individual in real-life situations.

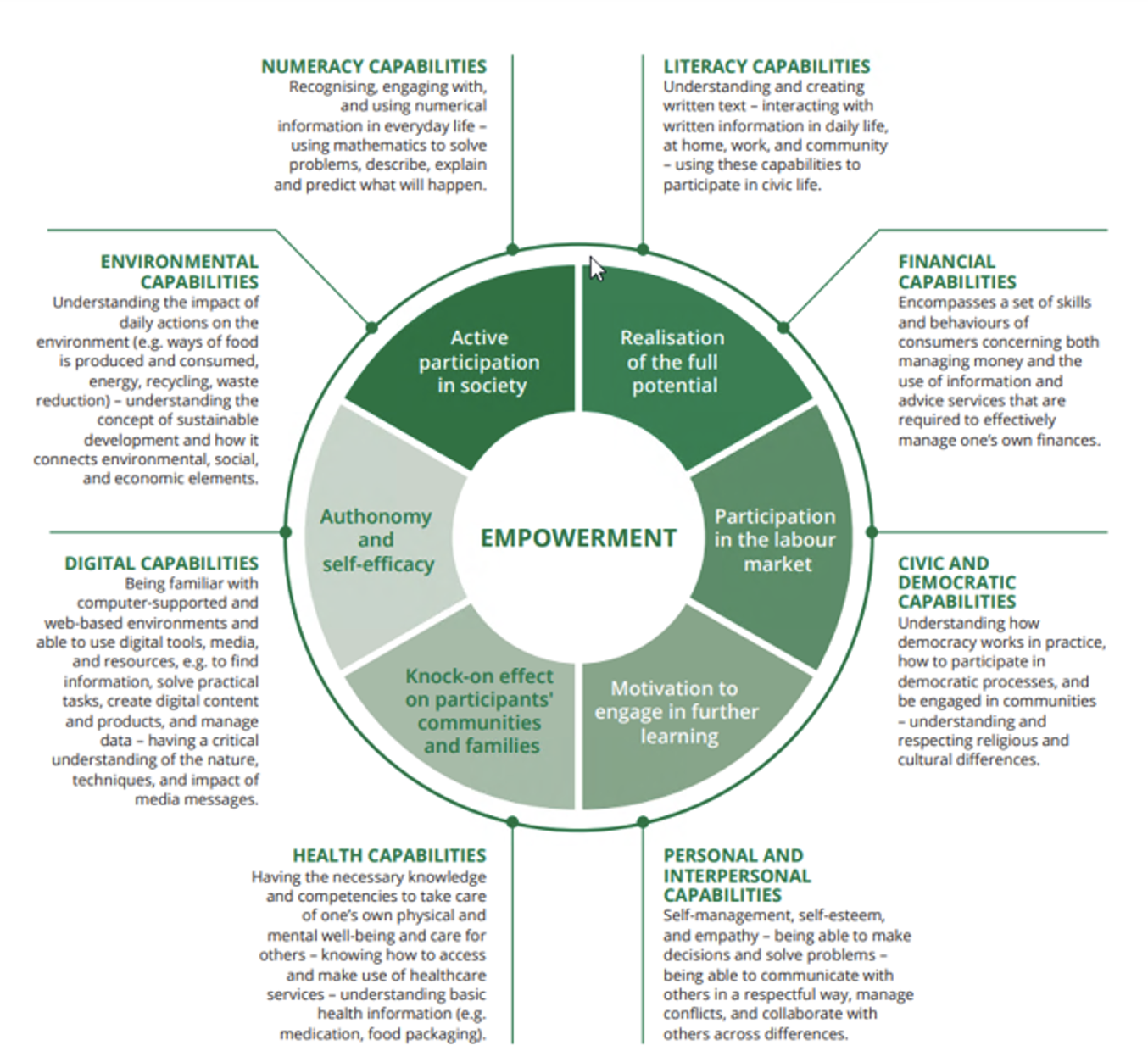

© Javrh et al, 2018, p. 5.

The term ‘capabilities’ has been proposed with the purpose of upgrading the definition of (key) competences. In this respect, the LSE report clearly emphasises that the critical and ethical dimensions are integral parts of the development of (key) competences, which are represented by the term capabilities.

According to LSE, understanding the capabilities does not depend on the context. Regardless of specific circumstances, they allow functional responses and actions in a wide range of different activities based on critical judgement. They are transferable among various professions and, above all, they enable individual development and active participation in work and society. Life skills are not always learned through education but are often acquired through experience and practice in daily life. They are one of the principal gains of adult learning and education alongside literacy and numeracy, practical skills (such as digital skills) and cultural learning.

The LSE learning framework offers a consistent framework for life skills learning that is applicable across Europe. The framework aims to put in practice the common understanding of life skills by defining eight key types of capabilities for life and work. The eight types of capabilities in the learning framework are as follows: numeracy, literacy, financial, civic and democratic, personal and interpersonal, health, digital and environmental capability. The combinations of different capabilities in general empower adults to become lifelong learners, to solve problems, to manage their lives and to participate in the community. This in reality means, for example, taking care of their physical and mental health, actively contributing to their well-being, mastering financial matters and coping with the digital environment.

© Javrh et al, 2018, p. 6.

The knowledge, skills and attitudes described in the framework take account of a range of international and European national competence frameworks and build on the European Reference Framework of Key Competences for Lifelong Learning, which supports learners of all ages in developing key competences and basic skills for learning. The capabilities included in the framework also reflect LSE partner input on national and local content, for example existing curricula and other relevant resources relating to specific capabilities, and are influenced by LSE project research on good practices and tools. The framework offers links to these resources for each capability area.

For adult education practitioners, the framework offers two aspects, difficulty of skill/capability level and familiarity of context for each capability, which allows for a range of starting points and supports the recognition of learners' progression. The framework is available in English, Slovenian, Danish and Greek.

There is an acknowledged overlap between some capabilities, for example numeracy and financial, digital and literacy and financial etc. This reflects the real-world interrelatedness of life skills. The framework begins with personal/interpersonal capability as this describes the skills, knowledge and attitudes which underpin all the capabilities. The framework is not intended to be exhaustive or prescriptive. Rather, it is presented as a starting point which can be added to and adapted to address the needs and requirements of different groups of learners. Equally, it is not presented as a programme of learning that learners work through from start to finish; learning should be prioritised so that the capabilities selected reflect learners' needs.

In conclusion

Our vision is that in the future every educational endeavour will have to ask itself whether and to what extent it promotes learning activities that help develop life skills that are vital to coping with the key issues of one’s life and survival.

Existing practices have shown that life skills can be systematically acquired and reinforced through non-formal and informal learning settings. The focus is on empowerment of adults through meaningful learning.

The research evidence and adult education practice clearly show that basic skills such as numeracy, literacy and digital skills are foundations for lifelong learning and also for the development of capabilities for life and work. It is essential that the development of integrated policies as well as holistic approaches and programmes for the development of basic skills of adults in the EU are supported.

Life skills cannot be learned in an abstract and theoretical way – the individual must collect, probe and discuss his experience where it happens in real life. It is important not to forget the contextuality of life skills, because this is the main reason for the success of life skills learning. Life skills need to be adapted to the specific contexts of each country, group and individual.

Life skills are in constant evolution in terms of individual, economic, social and cultural contexts. There are bound to be individuals and groups who cannot attain some life skills.

About this blog

This blog is based on a key note lecture at the EPALE and Erasmus+ Conference 2022: "Life Skills as a Focus in Adult Education"

Sources

European Commission (2017). European Pillar of Social Rights, Publications Office, 2017. See: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2792/95934.

European Commission (2020). European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience.

European Commission (2021). The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan. Porto Social Summit See: https://www.2021portugal.eu/en/porto-social-summit/action-plan/ .

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

Illeris, K. (2014). Transformative Learning and Identity. Routledge.

Javrh, P., Mozina, E. et al (2018). The Life Skills Approach in Europe, Summary of the LSE analysis. See: https://eaea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Life-Skills-Approach-in-Europe-summaryEN_FINAL_13042018-1.pdf.

OECD (2019). Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey on Adult Skills. Publishing, Paris.

Ostrom, E. (1990). In Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Sen, A. and Nussbaum, M. eds. (1993). The Quality of Life. Clarendon Press Oxford. See also: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0198287976?psc=1&th=1&linkCode=gs2&tag=worldcat-21&asin=0198287976&revisionId=&format=4&depth=1 .

Unicef (2019). Comprehensive life skills framework, Rights based and life cycle approach to building skills for empowerment. See: https://www.unicef.org/india/media/2571/file/Comprehensive-lifeskills-framework.pdf .

Life Skills for Adults

I enjoyed reading this and I agree with the author on the importance of teaching life skills in adult education - and the need to adapt life skills programmes to suit the individual and the evolving nature of our world.