Learning in the work environment – thoughts and suggestions for employment for refugees which promotes learning and integration

Reading time approximately 15 minutes – read, like, comment!

Original language: German

1. Informal learning and learning in the work environment

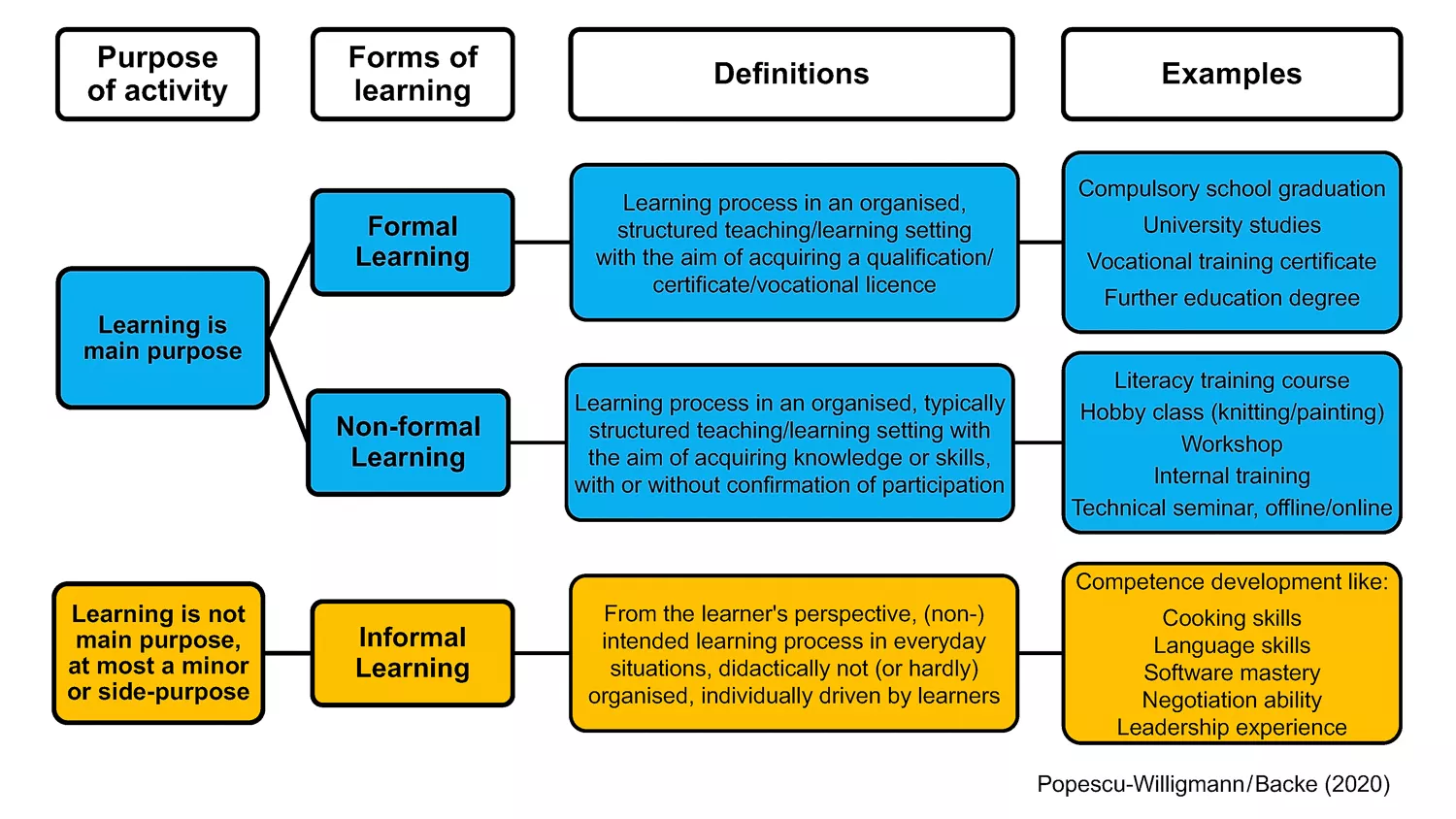

“Informal learning” (see illustration) refers to the acquisition of knowledge, skills and competencies outside of educational institutions and formal educational formats such as courses and seminars which are explicitly designed for learning purposes. Informal learning takes place in the most diverse everyday circumstances. It occurs in both private settings and work situations. Informal learning is experience-based learning without a curricular framework and, as a rule, without certification for the learning process and learning outcome. The work environment represents one important environment for informal learning in the context of continuing education for adults. It refers to both the immediate workplace and the broader organisational framework in which the workplace is incorporated.

Informal learning in the work environment is far more important than formal learning arrangements when it comes to the development of competencies which are relevant to an employee’s occupation. As their competencies develop, employees also improve their employability, i.e, their ability “to participate in the employment system. […] Employability gives people the power to guide their own professional development – and thus enables them to lead a self-determined life in a society based on the division of labour” (Popescu-Willigmann/Nenkova 2019, p. 64). The major influence of informal learning has been demonstrated by, among other sources, an international study from 2015 (De Grip 2015). As an employees’ competence profile improves, employers also benefit from the growth in creativity and productivity.

Although informal learning often occurs incidentally as a by-product of activities carried out in a work environment, there are many ways in which employers, by making sure the workplace is designed to promote learning, can support learning and strengthen the learning effect. A workplace that promotes learning:

- is embedded in an active and constructive learning culture which is tolerant of mistakes,

- includes tasks which promote learning,

- has managers who act as learning coaches and moderators of the learning and work process,

- makes use of team interaction and methods which stimulate both individual and collective learning,

- provides working, learning, knowledge and social spaces for informal learning,

- supplies learning supportive aids and resources and

- both enables and motivates collective learning experiences.

It is important that staff, in addition to possessing the knowledge, skills and abilities directly relevant to their own work, also understand the company, its goals and strategies, and its structures and processes. They need to be able to see their own work as part of the company’s broader value chain and be able to understand the significance of their actions in helping the company achieve its goals. This creates a sense of unity and fosters employees’ sense of responsibility and involvement. For this reason, transparency and openness on the part of the management – as promoters of the company – with respect to employees are also important aspects when it comes to learning in a work environment.

Informal learning is becoming ever more important for companies: The market conditions for companies are evolving just as dynamically as the demands on the workforce. Rapid technological growth and the increasingly global, interlinked nature of the world of work are resulting in numerous and complex changes and learning requirements. It is thus increasingly important that workers possess the meta-competence of being able to learn, in order to ensure that they keep pace with the latest changes and also further develop their competence portfolio. This does not only apply to knowledge-intensive areas of work. Policy makers have now also recognised the value of informally acquired knowledge and abilities: The identification and recognition of informally acquired competencies now occupies an important place on the agendas in European countries. The successful integration of foreign employees into the labour market, as well as the strengthening of labour mobility via the recognition of competencies on international labour markets, promises to help compensate for the shortage of skilled labour, to reduce the risks of demographic change and to lighten the burden on social welfare systems.

Due to time and cost factors, as well as the rapidly changing nature of requirements, learning in the work environment rather than in external learning settings offers direct economic benefits in addition to the benefits represented by the increase in personal competencies and employee motivation. Furthermore, it is difficult to integrate externally-acquired knowledge into established structures and processes. For this reason, learning and changing “from within” – as in the case of informal learning, which occurs incidentally and in a practice-based context – has greater potential for implementation. The concept of the learning organisation is unthinkable without internal learning processes. In addition, external learning settings and formal learning environments are now far less necessary, as digital technologies increasingly allow learning online and virtually anywhere in the world with access to the internet.

In addition to the numerous positive effects on companies and employees, strengthening the workplace as an environment for learning and emphasising the company as a learning organisation can assist in the integration of people from abroad[1]. We will now look at informal learning in the work environment with respect to the employment of refugees. Firstly, we will consider specific learning requirements and then we will detail suitable learning arrangements to meet these requirements.

2. Refugees’ learning needs

When it comes to employing people from countries with different education and labour market systems, especially non-EU nationals, identifying and recognising informally acquired competencies plays a vital role. This is particularly the case with respect to refugees, who are usually non-EU nationals. Our definition for “refugees” is taken from Popescu-Willigmann/Remmele (2019, p. 19), who mention aspects which are relevant to education and social work as well as to human resources management. The term “refugees” refers to people

- “who have recently arrived in a destination country,

- have fled from their home country for a variety of reasons,

- have mostly migrated under extremely difficult and dangerous conditions and

- are subject to specific legal conditions in their country of destination, frequently live in uncertain circumstances which are physiologically limiting and limited, and psychologically challenging, and restrictive with regard to societal participation, all of which determines the life they may lead.”

Refugees often have only incomplete documents that would support integration into the education and employment system. Furthermore, the way that qualifications and professional experience are acquired in other countries is often subject to differing systems with their own logic. It is therefore necessary to assess qualifications and experience and determine how they correspond to the system in the host country. This is why there is a growing emphasis on competencies which are supposed to summarise formally, non-formally and informally acquired knowledge and skills of individuals.

Informal learning in the workplace is an excellent tool for getting people from abroad and particularly refugees involved in practical employment, as it:

- helps to overcome formal obstacles with respect to education and employment,

- allows immediate learning results and learning success which are beneficial for social and professional integration,

- prevents the loss of competencies (de-skilling) due to lack of use and builds on the existing competence portfolio of learners to make them employable in new or updated ways,

- motivates and thus promotes integration and learning among learners who then experience “recognition” and meaning regardless of the documents,

- provides a high transfer value, insofar as the work environment allows this, and

- has relatively low costs due to its integration into the work context, and, due to gains in productivity on the part of the individual employees and the spill-over effects of new knowledge in the team, amortises its costs faster than formal learning settings or as workplaces that either do not foster learning or even prevent it.

However, are there specific learning needs – and learning methods – which apply to recent arrived people from abroad compared with natives or people from abroad who have been living in a country for a longer period of time? A differentiated “Yes” seems appropriate as an answer. This is because a learning need is derived from the respective requirements of a life situation or task and presents itself as a gap which, when compared to the requirements, results from the existing previous knowledge and skills of learners.

In the case of recently arrived people from abroad, obvious learning requirements exist, above all, in general areas of life such as language and literacy, “cultural techniques”, and familiarity with stakeholders, structures and processes in social space. Basic education strategies help to address such questions relating to the requirements of everyday life which “make a self-determined life and active participation in society possible” (Remmele/Popescu-Willigmann 2019, p. 107). Refugees can find such educational offers in the context of so-called initial orientation courses. Remmele and Popescu-Willigmann (2019) identify the following basic education areas as relevant when it comes to helping almost all recently arrived people from abroad find their feet in a different society:

- language and literacy

- basic socio-cultural education

- basic consumer education

- basic employee education

Individual learning requirements are identified by analysing the prior education of an individual and exactly what it is they need to learn. In the case of refugees, it is vital to stress that assumptions about their skills and requirements, and thus their suitability for certain types of work, cannot be made purely on the basis of their attribute as refugees:

“With respect to learning preconditions, people with a refugee background have essentially just as broad a spectrum of goals, desires and motivations, of talents, knowledge, skills and abilities and learning competencies, as well as fears and inhibitions, as any other (adult) learners.” (Popescu-Willigmann/Remmele 2019, p. 21)

There are thus, in addition to the previously mentioned general areas of learning, further general and occupation-specific learning requirements which result from the educational background and experience as well as from the particular conditions of individuals. With respect to educational background, literacy levels, educational attainment and educational experience are among the starting points for determining occupational aptitude or occupational learning needs, in addition to work experience and the competencies that may need to be determined in a recognition procedure. The education and employment system from which individuals come needs to be considered. The systems may differ significantly from systems in the new country of destination of a person from abroad (see Popescu-Willigmann/Nenkova 2019, p. 69–72) and thus require different forms of approximation, adaptation, translation or adaptive learning. In other words, it is important not to regard refugees as a homogeneous group when it comes to their employability.

At most, similarities may be identified in shared or similar living circumstances in the new country and social environment. These aspects, too, need to be considered when it comes to staff deployment and staff management, including learning in the work environment. Refugees’ living situations are oftentimes influenced by:

- the causes they fled from their home country and their experiences while fleeing

- their residence status in the destination country and the associated rights, obligations and obstacles to participation (Nenkova 2019 provides a good overview for Germany)

- uncertainty regarding the lives they will now lead

- language challenges in the new country

- new societal rules and customs in practically all areas of life

- physical and psychological health conditions

- the family situation and the impossibility or difficulty of reunification with family members in the diaspora or in a war or crisis zone

- generally, the situation in an unknown environment

- the frequent change in status that comes with a new beginning as a refugee in a destination country

Existential questions which refugees have to face include the outcome of the asylum procedure, the impossibility or difficulty of reunification with family members in the diaspora or in a war or crisis zone, or the influence of and dealing with the consequences of (often unrecognised and untreated) trauma (Popescu-Willigmann/Nenkova 2019, p. 72).

While the life situation – at least – in the period immediately following arrival as a refugee in a new country is heavily influenced by this experience, it should not be viewed as an exclusively negative or limiting experience. On the contrary, refuges still possess their learning, educational and employment history, and also possess intercultural resources due to their international experience (not least as refugees). Furthermore, while fleeing, they have frequently coped with profound communicative, psychological and social challenges, and developed personal attitudes, behavioural competencies, creativity, as well as a focus on finding solutions and achieving goals (Popescu-Willigmann/Remmele 2019, p. 22).

3. Suggestions for learning in a work environment

It is clear from the above that: Learning at work provides a low-threshold way of acquiring, updating and improving knowledge and abilities relevant to working life. It allows employees to develop their capabilities in a practice-based manner as well as faster and more thoroughly than is possible in artificial learning settings. With respect to new colleagues and especially people from abroad, it is interesting to note that learning in a work environment offers job-related benefits and also promotes integration within a team. New employees who have come from abroad learn “cultural techniques” in the company as well as local and country-specific customs. Orientation in the broader social environment is also learned, whether via discussion and explanations or through interaction with stakeholders such as customers and suppliers. New employees enrich the team on a personal as well as on a professional level. They bring new perspectives and experience and, by introducing a fresh approach to existing aspects, can help employers spot new potential for innovation. For employees of all (formal) education backgrounds, holistic learning in a practice-based setting offers enormous potential for acquiring new knowledge and skills.

[1] Authors’ note on the English text: We use the term “person/people from abroad” when mentioning somebody who is a non-native in a country where they currently live, be it temporarily or lasting. Thus, we avoid the differentiation between “migrants”, “immigrants”, “refugees” or “asylum seekers” which would add no value to the understanding of our text’s scope. When we refer to points that we find particularly relevant for refugees (not excluding asylum seekers) we mention “refugees”. See IRC’s explainer if you are interested more deeply in the words’ meanings: https://www.rescue.org/article/migrants-asylum-seekers-refugees-and-immigrants-whats-difference (01.04.2020)

© StartupStockPhotos on Pixabay

The logic behind quickly and productively integrating employees who have recently arrived in a country as refugees into their new work is self-explanatory. By firmly embedding (institutionalising) productive, informal learning opportunities, employers can reliably support employees in acquiring knowledge and ensure that learning success is far less dependent on chance. Of course, this does not make formal and non-formal learning offers redundant. The right learning opportunities, carefully designed and integrated into the work environment, allow (new) employees to:

- acquire, expand or reinforce specialist vocabulary,

- learn working methods and how to use equipment and tools, and

- to establish or extend their capacity to act in further technical, conceptual, organisational or social fields.

In addition to learning opportunities which are directly related to work tasks or occupation, learning arrangements relevant to the job or the workplace can also address the personal learning needs of new employees. This would take place primarily in discussions within a team as well as in learning arrangements intended to serve this purpose. In any case, the employer must provide resources for informal learning in the workplace (e.g. space, time and material) or at the very least not limit the possibilities (for example due to overly restrictive or limited work tasks).

Exploiting the potential for informal learning in the work environment brings many benefits. By supporting integration in the new country and social environment, some of the circumstances that make refugees’ lives difficult can be overcome or at least mitigated. Being accepted by colleagues and participating in society via social activities and connecting to local groups can help to overcome social isolation, the feeling of being totally reliant on oneself in a new country, and exclusion from the local community. Rapid orientation in the social environment makes people more self-assured and fosters both the independence and self-confidence of newly arrived people from abroad. This is achieved by acquiring the capacity to act in more or less substantial as well as in everyday live areas such as the health system, public transport, shopping and access to cultural activities, and by getting to know the city and its institutions.

Learning opportunities can be incorporated in the work environment in various ways, including:

- Organisationally, via framework conditions in the company which enable learning either explicitly (consciously) or incidentally as a by-product in the course of working practice, and in additional ways such as on the level of the company structure, work activity, and via educational interventions aimed at adults (Salman 2009, S. 98)

- Object-based, via aids with learning quality for work, explicitly for learning or for support

- Spatially, via the possibility of using the workplace as a learning venue and via spaces in which learning is possible individually or collectively in groups

- Medially, via the availability of various learning media and information

- Personally, by providing interaction which supports learning, including advice from superiors or colleagues, supervision or coaching

- Temporally, via the availability of time to learn while working or alongside work activity but during working hours

There are countless ways in which a work environment can be adapted to promote learning. We will now provide a list of some key terms to illustrate this. As the range of methods is almost unlimited, we will direct you towards further information and toolboxes at the end of this article.

- Design of the enterprise, e.g.: clear goals and visions, a culture that promotes learning by tolerating mistakes, transparency and open communication, appropriate arrangements concerning available free areas and autonomy, shaping the organisational structure and processes in a way that promotes learning, knowledge management, integration of staff development and organisational development, reliable tools and technologies, management philosophy and an approach which promotes learning (with institutionalised formats such as mentoring, coaching, management feedback, etc.)

- Design of work activities, e.g.: tasks design which promotes and stimulates learning, project work, thorough initial training and instruction from superiors and colleagues, enriching work activities (via job rotation, job enlargement, job enrichment), the chance to observe others working, the possibility to learn at specific events (congresses, conference, fairs, working and experience groups, etc.)

- Group formats which stimulate learning, e.g.: Team work, counselling through colleagues, learning groups, role plays, simulation games, quality circles, learning workshops, learning islands and other explicit learning spaces, continuous improvement process, simulations, communities of practice

- Educational counselling offers, e.g.: Learning counselling, coaching and support (learning techniques, language coaching, etc.), tools for recording learning progress, learning success or growth in competencies (Salman 2009, p. 98), support for the recognition of informally acquired competencies

- Provision of media which support learning, e.g.: Specialist literature (books, magazines, glossaries, etc.), literature for learning (sector-specific language guides), digital learning offers (external and internal e-learning offers such as computer-based training, CBT, and learning platforms, MOOCS), documents for work, instruction and description which contain a learning aspect (e.g. in plain language), pictograms, digital information offers (newspapers, intranet, news platforms, etc.), learning cards, TV and radio, communication forums, social media and virtual communities

4. Conclusion:

We have highlighted the importance of informal learning in the work environment and pointed out the particular benefits towards the integration of refugees. Informal learning requires deliberate actions and resources so that it can be implemented sustainably and independently of individuals. The commitment of the management must be openly demonstrated, supported and implemented by all leaders and managers . Employees also have a responsibility to exploit the learning potential of their workplace and to be actively involved in shaping learning opportunities. Likewise, all members of a company are responsible for helping to integrate new colleagues.

While informal learning offers tremendous advantages, it is important to bear in mind that formal and formalised learning opportunities are also required in order to fully meet a company’s learning requirements. Ideally, formal and informal learning are combined to achieve the highest possible learning outcome. The combination of work and learning infrastructures (Dehnbostel 2014) constitutes the modern approach to work in a dynamic and constantly changing environment.

About the authors:

Silvester Popescu-Willigmann is Head Project Management at the Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation in Switzerland and a publicist. He was Managing Director of the Refugee Centre Hamburg (Flüchtlingszentrum) until spring 2018.

Julia Backe is, among others, a certified Systemic Coach and provides coaching, supervision and teambuilding. She also works in the field of continuing education and consulting for professionals and management as well as for clients in a Swiss Foundation for persons with cognitive impairment.

Related articles:

- Work-based Learning in Europe

- Strategic Inclusion of Migrants in Adult Learning Programme Development

Further reading

- Cedefop (2015): European guidelines for validating non-formal and informal learning. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union,. Cedefop reference series; No 104. (https://dx.doi.org/10.2801/008370) (19.03.2020)

- OECD: „Recognition of Non-formal and Informal Learning”

- (https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/recognitionofnon-formalandinformallearning-home.htm) (19.03.2020)

- Popescu-Willigmann, Silvester/Remmele, Bernd (Hrsg.) (2019): ‚Refugees Welcome‘ in der Erwachsenenbildung. Adressatengerechte Programmgestaltung in der Grundbildung. Bielefeld: wbv Media.

- Salman, Yvonne (2009): Bildungseffekte durch Lernen im Arbeitsprozess. Bielefeld: wbv.

Further internet references

- Anabin – Infoportal zu ausländischen Bildungsabschlüssen (https://anabin.kmk.org/anabin.html) (19.03.2020)

- Branchenbezogene Materialien zum Deutschlernen (https://www.deutsch-am-arbeitsplatz.de/fuer-den-unterricht/arbeitsplatzbezogene-materialien.html) (19.03.2020)

- Charta der Vielfalt (https://www.charta-der-vielfalt.de/en/) (19.03.2020)

- Deutsch für die Arbeit – Ein Wegweiser (https://www.netzwerk-iq.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Downloads/Fachstelle_Berufsbezogenes_Deutsch/03_Publikationen/LFW-quick-guide-DE.pdf) (19.03.2020)

- Initiative Neue Qualität der Arbeit: (https://www.inqa.de) (19.03.2020)

- KMU Toolbox für Geschäftsführungen und Personalverantwortliche (https://www.netzwerk-iq.de/foerderprogramm-iq/fachstellen/fachstelle-interkulturelle-kompetenzentwicklung/angebote/fuer-kmu/kmu-toolbox) (19.03.2020)

- Language for Work (https://languageforwork.ecml.at/) (19.03.2020)

- Netzwerk Integration durch Qualifizierung (https://www.netzwerk-iq.de/) (19.03.2020)

- ProfillPass (https://www.profilpass.de/) (19.03.2020)

- REST-Projekt: Erfolgsgeschichten – Beispiele gelungener Integration von Geflüchteten in Unternehmen (https://rest-eu.org/wp-content/uploads/REST_good_practice_german.pdf) (19.03.2020)

Sources

- De Grip, Andries (2015): The importance of informal learning at work. IZA World of Labor 2015: 162 doi: 10.15185/izawol.162. https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/162/pdfs/importance-of-informal-learning-at-work.pdf?v=1 (19.03.2020).

- Dehnbostel, Peter (2014): Perspektiven für betriebliches und eLearning: Informelles Lernen im Prozess der Arbeit. In: Community of Knowledge. https://www.community-of-knowledge.de/beitrag/perspektiven-fuer-betriebliches-und-elearning-informelles-lernen-im-prozess-der-arbeit/ (19.03.2020).

- Nenkova, Yana (2019): Aufenthaltsstatus als Inklusions- und Exklusionsaspekt. In: Popescu-Willigmann, Silvester/Remmele, Bernd (Eds.): ‚Refugees Welcome’ in der Erwachsenenbildung. Bielefeld: wbv Media, p. 40–51.

- Popescu-Willigmann, Silvester/Nenkova, Yana (2019): Teilhabe an (Aus-)Bildung und Arbeit. In: Popescu-Willigmann, Silvester/Remmele, Bernd (Eds.): ‚Refugees Welcome’ in der Erwachsenenbildung. Bielefeld: wbv Media, p. 64–78.

- Popescu-Willigmann, Silvester/Remmele, Bernd (2018): Lernen im Kontext von Flucht und Ankommen. Grundbildung als Einstieg in die neue Lebenswelt. weiter bilden (03/2018), 17–21. https://www.die-bonn.de/doks/weiterbilden/2018/fluechtling-01.pdf (19.03.2020).

- Salman, Yvonne (2009): Bildungseffekte durch Lernen im Arbeitsprozess. Verzahnung von Lern- und Arbeitsprozessen zwischen ökonomischer Verwertbarkeit und individueller Entfaltung am Beispiel des IT-Weiterbildungssystems. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann Verlag. https://www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/publication/download/2036 (19.03.2020).

Comments

Ļoti konstruktīvs raksts, jau

Daudzas iespējas un resursi ir pieejami, daudzi bez maksas

Bēgļu apmācības

Paldies par jūsu atsauksmēm

Paldies par tik konstruktīvu

Prieks, ka ir minēts par to, ka šādā darba vidē atzīst konstruktīvas mācības, tostarp mācīšanos no kļūdām. Domāju, tas ir viens no labākajiem priekšnoteikumiem, lai darbinieki (it īpaši jaunie) justos droši, mācītos un attīstītos bez bailēm un šķēršļiem.

Uzskatu, ka tas ir lieliski,