Adult citizenship education in the UK: language competence and cultural identity

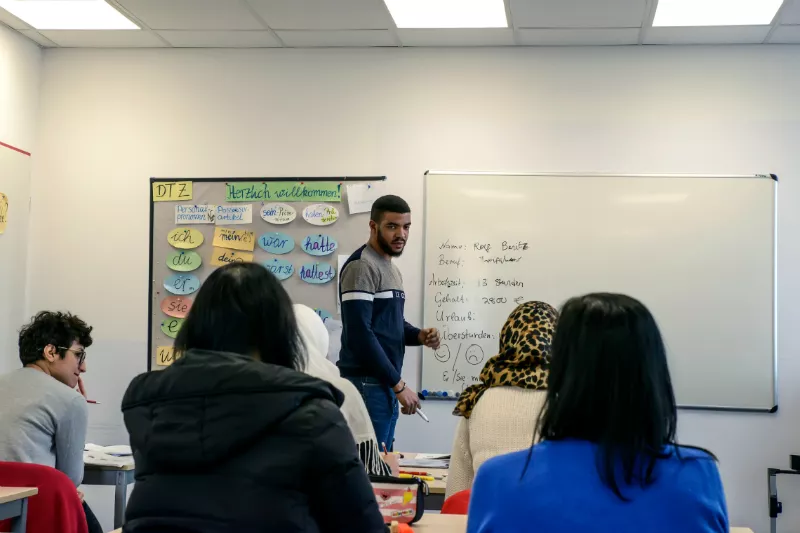

English teacher Qasir Shah reflects on the importance of language proficiency in migrants’ social integration.

Bernard Crick, the British political theorist, was instrumental in introducing citizenship education (CE) to compulsory education in the UK in 2002. Crick’s desire was to change the political culture of this country both nationally and locally. Two subsequent reports, from Crick-chaired committees, concerned the CE needs of 16-19 year olds and migrants to Britain; this affected the teaching of migrant language education courses (ESOL) at all levels by making it a requirement to include CE components in the ESOL curriculum.

Adult ESOL citizenship education (AECE) came about as a result of the British government’s concern about social unrest which took place in 2001 in three towns and cities with large ethnic minority populations. The roots of the riots were argued to lie in the lack of community cohesion, predicated upon a lack of shared values. So, the government argued for the need to develop a sense of civic identity and suggested that improved knowledge of the English language had an important role to play in achieving this. Indeed, English competency was seen as essential in the process of integration and the report therefore recommended unified language-with-civic-content programmes. In this way, language proficiency came to be associated with the migrant’s willingness, and ability, to integrate.

The effectiveness of adult ESOL citizenship education

So how effective has AECE been in changing the political culture of the UK? Unfortunately, it hasn’t, and there are several reasons for this. Neither the Adult ESOL Curriculum nor the handbook Life in the UK, provide an in-depth understanding of citizenship and British culture in its profound sense, and within the implementation of the policy greater emphasis was placed on promoting community cohesion and integration, than political literacy. There was also (and is) a lack of specialists to teach the subject, and it is also questionable whether ESOL students below B2 have the linguistic competence to study CE in a maximal sense.

It is also pertinent to ask how AECE enhances the migrant’s integration into British society, communities and workplaces when the majority of the adults with whom they will interact have had not one single lesson in their entire lives about concepts of citizenship. It is essential that CE be taught to all migrants, and all native adults, for it makes no sense to have the majority of native adult population of the United Kingdom ignorant of what citizenship means.

Identity formation and language competence

The reconstruction of the migrant's identity in their new society is important; the reconstructed identity is enriched by a deeper understanding of the host nation’s history, customs, culture, and legal and political systems. Learning the language of a country is inextricably linked to accessing civil freedom as well as understanding its culture and society. Consequently, it is not unreasonable to believe that greater knowledge of the host country would facilitate social integration and acceptance in the host nation. This discourse, which purports to promote inclusivity and social integration, is in fact premised on the fact that those speaking other than the dominant national language are perceived as being outsiders and not truly belonging to the nation. However, there is little evidence that citizenship and social integration are only possible with language proficiency in the host country.

Public virtues and the importance of language competency

There is an undoubted tension between promoting diversity and unity. But, to blame multicultural tolerance and celebration of diversity for a lack of community cohesion is to deny both the reality of transnationalism and super-diversity and the existence of supra-identities such as EU citizenship, and powerful multinational corporations, which make the idea of fostering national identity seem parochial. It is also to ignore the discrimination and structural inequalities that have prevented migrants and ethnic minorities from feeling at home, unless they completely renege their prior cultural/national affiliations.

It would seem that, contrary to much political rhetoric, fluency in the host language, and AECE are insufficient in themselves to foster integration, prevent social exclusion, and engender greater civic participation.

Qasir Shah has taught English language for over 19 years and for the last 16 years he has been teaching ESOL to adults. He also teaches academic English to graduate students. In addition, he is pursuing a PhD in philosophy of education at University College London. His areas of interests are educational policy in England, literacy, citizenship education, democracy, Confucian ethics and the role of the teacher.

Bardzo prawdziwe. Jednak