What a "beautiful" disaster: education and crisis situations

8 min read- like, share, comment!

First published in Polish by Marcin Szeląg

What do Hurricane Katrina, the tsunami in Japan, the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, war in Ukraine and the flooding in North Rhine-Westphalia all have in common? All of these events are examples of disasters: climate induced disasters, natural disasters, war, terrorism. Recollections of them evoke not only images of destruction, human tragedies, suffering and trauma, but also remind us of social mobilisation, which is linked to the need to combat the aftermath of disasters, and provide help to those affected. They are also a testing ground for lessons to be learnt for the future. While not all disasters can be predicted or prevented, past events can at least teach us how to limit their negative effects. In other words, there is a strong link between past disasters and education.

Photo by Marc Szeglat on Unsplash

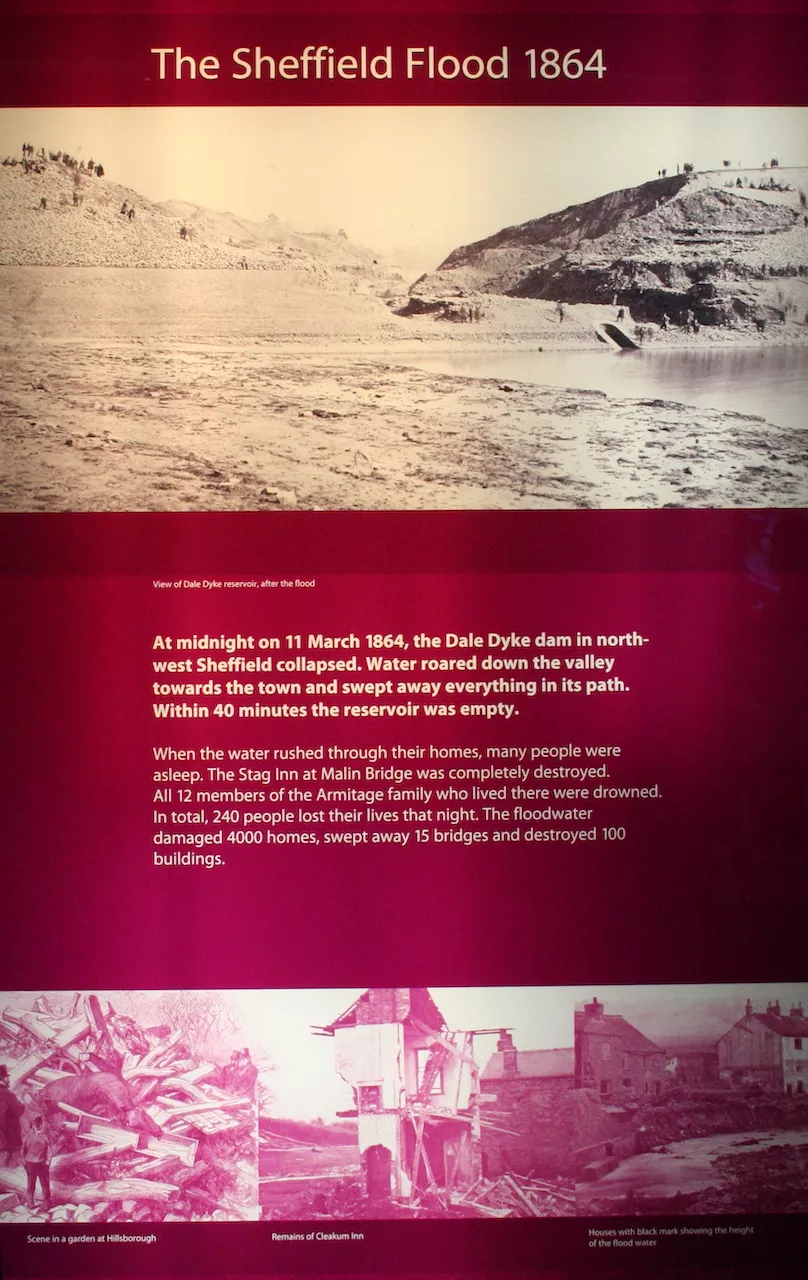

Because of that, the narration about the past very often includes examples of stories of spectacular disasters: floods, fires, earthquakes, terrorist attacks. They are treated both as turning points in the life of a given community, but also as a pretext for educational activities that could prevent or limit the impact of such events in the future. Stories of tragic fires, floods, earthquakes, and terrorist attacks can also be found in museums. These may be stories woven into a wider historical narrative about a city, as in the case of the Museum of London, which has a permanent exhibition dedicated to the city's fire of 1666, or the Weston Park Museum in Sheffield, which portrays the flood of 1864 and recalls its tragic victims. On the flip side, many communities commemorate tragic events caused by disasters by creating entire museums dedicated solely to those events. Examples include the 9/11 Memorial & Museum in New York dedicated to the events of 11th of September 2001, or the Flooded House Museum in New Orleans, which was established in 2016 to commemorate the victims and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina from 2005, as well as to raise awareness and campaign for better flood protection. An example of such an institution in Poland is the Fire Museum in Żory. It recalls the history of a town marked by numerous tragic fires, in which the Fire Festival has been celebrated since the beginning of the 18th century. The disasters served as a pretext to create an interactive educational exhibition. It presents issues of the dangers caused by fire and discusses issues of fire safety.

In the 21st century, the link between natural and anthropocentric (man-made) disasters is becoming increasingly clear. Apocalyptic floods and fires that are linked to climate change, such as those that hit Germany and Greece this summer, are affecting more and more countries around the world. The same is true of the terrorist threat or gigantic power grid failures, which mostly concern the countries of the Global North. On the one hand, areas of the world where spectacular natural disasters have occurred sporadically or not at all are rapidly shrinking; on the other, globalisation, digitalisation, social inequalities, cultural and religious wars are a breeding ground for extremists, populists, and autocrats, who do not hesitate to use the arsenal of terror to achieve their political goals.

Disasters therefore become important also in the realm of lifelong education. Organisations such as UNESCO, the European Commission and other international and national bodies highlight the role of education and learning as increasingly important - the key to being prepared for disasters. The main goal is the preparation for dealing with crisis situations, and the acquisition of the skills necessary to respond to disasters, particularly in countries experiencing natural disasters, such as New Zealand, Japan or the United States of America.

Strategies

When it comes to disaster risk education for adults, there are various strategies and policies which target entire communities or specific individuals. In Japan, for example, learning to be prepared for the arrival and impact of disasters is part of the government's lifelong learning policy. In New Zealand there is also an emphasis on educating communities, but from the bottom up. It is the responsibility of individual local communities, not the government, to develop their own solutions for addressing hazards and dealing with their impacts and consequences. Both of those countries have been subjected to major natural disasters, including earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. In countries that rarely experience disasters of such severity, there is less emphasis on educating communities. In the UK, for example, the government does advocate the social dimension of learning to be prepared for crisis situations, but the role of education is mainly concerned with the individual or the family unit. In Germany, there is a culture of volunteering, but there is an absence of any national or federal requirement for educating communities in this regard.

The memory of prior experiences

Regardless of the strategy chosen, a common thread in disaster risk education is the awareness of crisis situations experienced in the past. In teaching about disasters, knowledge of disastrous events which occurred in the past are an important element. Hence this type of education has a particular chance of success when it draws on the history and culture of a given community. By tapping into the collective memory of the community, people can draw on previous historical resources to shape their current experiences. This allows for efficient organisation, minimising damage, and relatively 'normal' functioning, as in the case of the Japanese island of Kyushu, which for years, with greater or lesser intensity, has been affected by the eruptions of the Sakurajima volcano. When the islanders are informed by the local Meteorological Agency about the scale of the eruptions and the direction of the wind, they take immediate action. Based on prior experience, they close the windows of their houses and cover their crops to protect them from the volcanic ashes. The authorities provide equipment, tools and support to clear the debris. The alert level is regularly assessed and monitored by the Meteorological Agency. Daily life is adapted to living in the vicinity of an active volcano. This makes it possible not only to function, but to limit the long-term emotional effects associated with the constant threat of further eruptions.

The elements

Cultural institutions such as museums and heritage centres are particularly helpful in dealing with emotional impacts, as they provide space where individuals can attempt to manage their emotions and work through them. For the reasons mentioned earlier, museums in countries frequently hit by disasters have the most experience in this area. In Japan, after the Niigata Chuetsu earthquake in 2004, on the island of Honshu, the Chuetsu Earthquake Memorial Corridor was created. Comprised of four museums that operate as cultural centres, it preserves the memory of the event and carries out educational activities to raise awareness of the various aspects of the earthquake and, above all, focuses on the emotional recovery of the affected community. In New Zealand, in turn, there is the Museum of New Zealand / Te Papa Tongarewa, where a unique structural design protecting the building from the most severe seismic shocks is a part of the tour programme. It is complemented by educational activities aimed at strengthening the mental health of the earthquake-prone community. In Europe, there are also initiatives directed to those affected by natural disasters. In 2010, the Natural History Museum of Crete developed a project aimed at helping children, especially those with physical disabilities, to reduce the negative emotional impact caused by major natural hazards (earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis). The project involves increasing the knowledge and competences of teachers, parents, volunteers, and emergency services through best practices learned from previous disasters, which raise awareness of the risks, but also show how to deal with the emotions of children, who, as a group, are the most vulnerable and most exposed to the consequences of disasters.

Plagues

Museums do not limit their activities to natural and climate-related disasters. Epidemiological threats are no less traumatising and provide a reservoir of experiences that can be used; both as therapeutic tools and as an educational resource. In 2013, the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences created the Oral History Archive dedicated to the 2003 SARS epidemic, consisting of short films featuring people involved in the fight against the virus. They provide a detailed record of experiences and reflections used during the subsequent pandemics, and often provided the participants with an opportunity to work through traumatic memories. A few years later, in the wake of the COVID-19 disaster, traditional Asian dancers in India, Indonesia and Thailand drew on indigenous cultural traditions. They added new elements to their performances to promote social distancing and hand washing. They also addressed the emotional trauma caused by the Coronavirus epidemic.

Wars

Armed conflicts and terrorism represent a boundless area of suffering, harm, misery, tragedy, and the associated traumatic experiences. Still, they are often presented in museums as the natural pattern of the history of nations, the backdrop of stories of national heroes and the crucible of character formation. In a sense, this has its historical justification, because, as was evocatively shown at the Europe - Our History exhibition in Wrocław's Centennial Hall in 2009, the history of the continent is a timeline of permanent war interspersed with short periods of peace.

The disasters of war, however, can give rise to very different stories that are stripped of their heroic dimension. The Conflict Textiles project developed in collaboration with the University of Ulster includes exhibitions, workshops, and a digital archive. It is a collection of textiles with embroidered stories of violations of human rights, armed conflicts, declarations of resistance and expressions of hope. Some of these textiles were created as a product of therapy for people who have experienced war or military crises. This project aims to raise awareness of the importance of human rights and draw attention to examples of their violation. A similar goal is pursued by the Museums for Peace. It is a worldwide network of institutions that, through the involvement of their recipients, promotes a global culture of peace by collecting resources and interpreting the life stories of individuals, the work of peaceful organisations, as well as historical events in the spirit of peace. Unlike the Sites of Conscience, as a rule, these are not established in historical places. The latter are set up in places where human rights have been violated in the past. They are established to promote justice and document the atrocities of the past. Sites of Conscience form an international coalition that supports post-disaster reconstruction. Compared to Peace Museums, they focus primarily on the future. Working through traumatic experiences provides a strong rationale for preventing a future reoccurrence of past disasters by mitigating their root causes.

Accommodating the social memory of disasters allows people to remember events that have been significant in the history of a given community. It creates a reservoir of practices and experiences that influence the future and allow for the healing of emotional wounds caused by crisis situations. If, therefore, one can see any "beauty" in disasters, it is not due to the mesmerising force of nature exposed by the raging elements, or the magnetism of historical processes that caused countries or nations to clash, but above all due to their educational and therapeutic potential, cultivated by museums for the purpose of lifelong learning.

dr Marcin Szeląg – arts historian, museum educator and curator, assistant professor at the Faculty of Arts Education and Curatorial Studies of the University of Arts in Poznań, director of the Regional Museum in Jarocin. Ambassador of EPALE.

Bibliography:

Four Creative Ways Traditional Asian Dance Is Being Used To Promote Social Distancing and Hygiene, w: Asia Blog, https://asiasociety.org/blog/asia/four-creative-ways-traditional-asian-dance-being-used-promote-social-distancing-and [dostęp: 30.08.2021].

Disaster Risk Reduction: UNESCO’s contribution to a global challenge. UNESCO, Paris 2015 https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233348 [dostęp: 30.08.2021]

Disaster risk reduction: Increasing resilience by reducing disaster risk in humanitarian action. European Commission, Brussels 2013

McGhie, H.A. Museums and Disaster Risk Reduction: building resilience in museums, society and nature. Curating Tomorrow, UK. (2020), http://www.curatingtomorrow.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/museums-and-disaster-risk-reduction-2020.pdf

John Preston, Charlotte Chadderton, Kaori Kitagawa & Casey Edmonds, Community response in disasters: an ecological learning framework, International Journal of Lifelong Education, 2015, 34:6, 727-753, DOI: 10.1080/02601370.2015.1116116, https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2015.1116116

Comments

I thank the author for this…

I thank the author for this article. In the context of today's events, this article touched me deeply. We are all affected by crisis situations, and we tend to focus on the negative consequences (and I think this is normal).

For some reason I had not thought before about what I have learned from crises. I think it's because I live in a place where there are no earthquakes, no tornadoes, no tsunamis, no volcanic eruptions. There is no war.

The biggest crisis I have had in my 32 years of life is Covid-19. What have I learned? To adapt, work more creatively, to protect myself and others and to appreciate lively communication more. I hope that this will remain the biggest crisis of my life, because there are a lot of terrible things happening in the world.

Thank you for your comment…

Thank you for your comment. I strongly believe that Covid-19 will remain the biggest crisis of your life. It is important that we can learn not only from good but also bad experiences. The War in Ukraine has already taught many of us in Europe how important is to help war refugees and that we need to rethinking (more seriously than during pandemic) our life priorities.

Katastrofos kaip terapijos priemonė ir kaip mokymosi išteklius

Labai įdomus ir kiek netikėtas požiūris ir išryškintos sąsajos tarp švietimo ir įvairaus pobūdžio katastrofų kaip edukacinių priemonių, kurių pagalba galima ne tik ugdyti(s) istorinę atmintį, patriotiškumą, puoselėti savo tautos, šalies istorijos pažinimą, vertybes ir pan., bet ir panaudoti visa tai kaip terapijos priemonę, kaip priemonę, padedančią susidoroti ir su įvairių katastrofų sąlygotu emociniu poveikiu, mokytis įveikti, išgyventi jų metu ir po jų, o gal iš dalies ir pasiruošti ir būsimoms - taip ugdantis emocinį atsparumą (jokiu būdu, ne abuojumą, o kaip tik gebėjimą priimti ir suvokti, kas gali ir kas negali būti suvaldoma, keičiama ir pan.), gebėjimą greitai priimti sudėtingus sprendimus, konstruktyviai veikti ypač sudėtingomis, netipinėmis sąlygomis.