FROM TRADITIONAL CITIZENSHIP TO DIGITAL CITIZENSHIP

The origin of the “citizen” Word etymologically extends to Ancient Greece. This concept is mentioned in Aristotle's Rhetoric for the first time in written sources. The citizen word is derived from the word” cite“ (or “city“), which refers to the ancient Greek city-states. However, the concept of citizen had to wait for the French revolution to have its meaning as a political identity (Boineau, 1998). Therefore, "citizenship” concept with its current meaning has entered our lives in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Citizenship skills can be developed in-class and out-class activities. In several countries such as England, France, Italy, USA and etc., citizenship education is a part of fundamental national aim of education (Kerr, 1999). On the other hand, the EU expressed the importance of citizenship education by a series of policy initiatives such as Paris Declaration (European Commission, 2015) and the Key Competences Framework (Council, 2006).

“Citizenship education is a subject area which aims to promote harmonious co-existence and foster the mutually beneficial development of individuals and the communities in which they live.” (De Coster & Sigalas, 2017). Citizenship education includes (UNESCO, 1998);

educating people in citizenship and critical values such as human rights, peace and equality,

improving critical thinking and judgement skills and

being aware of individual and social responsibilities and acting responsibly

With the growing use of digital technologies everyday life, we faced an important issue, how better to prepare citizens to appropriate use of these technologies. As a result, a new concept has entered “digital citizenship”. A digital citizen is a person who can criticize online information, can communicate via digital technologies, can produce and consume in digital environment and complies with the ethical rules while conducting these behaviors and is aware of their rights and responsibilities.

Today, several communicative functions or services became available via internet technologies. For example, in Turkey, you can access to all public services offered by the government to citizens from a single online web site called as e-government gateway (Figure 1). This gateway provides 1767 e-services by 296 agencies. By using this portal you can access your cases and other judicial proceedings or can benefit from education, scholarship and test information and application services. Similarly, the gateway includes several components to offer services to the citizens through the easiest, most effective and fastest means possible.

Figure 1. The screenshot of e-government gateway

E- Pulse is also a new online health platform in Turkey that offer services to citizens and health professionals (Figure 2). This platform includes different kinds of health data such as hospital visits, prescriptions, reports, lab results or medication details of citizens. Thanks to easily access of these health data in one place, diagnosis and treatment procedures may be performed in faster and more effective manner.

Figure 2. The screenshot of e-pulse

For public transportation in Ankara (capital of Turkey), subway system is the fastest way to get anywhere. There are two subway train lines in Ankara, one for runs northwest-southeast and the other for runs east-west. Online technologies also make it easier to use the subway system. For example, payment can be done by paper fare tickets with magnetic stripes or any contactless debit cards (Figure 3). So if you have any contactless debit card, you do not even have to plan anything for payment procedure, just waving your debit card over the reader would be enough.

Figure 3. Payment through a contactless debit card

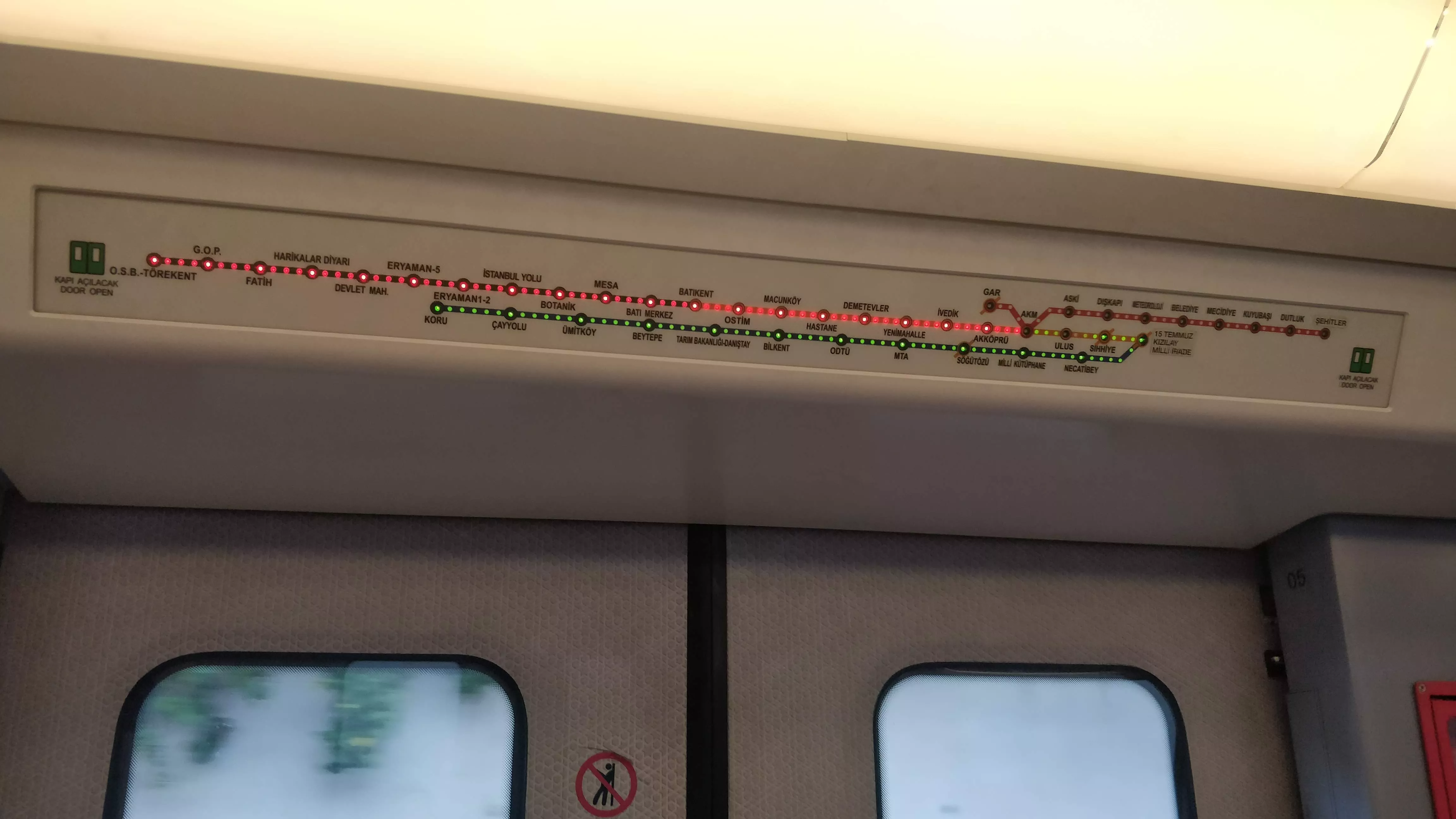

When you are using a subway, you can see the map of subway terminals (Figure 4). From this map,

you can track which terminal you are in or how many stops are left for the destination terminal. Color-coded navigation system exists in the map. All terminals that are not visited yet on the way are seen as red. When you head away from any terminal (A) to other one (B), the color of terminal (A) changes to green. So you do not need to ask any help for guidance to reach any terminal.

Figure 4. Map of subway terminals

Along with the adoption of governments to the internet era and educating digital citizens, most of the important problems such as citizens’ physical attendance or paper trails of heavy bureaucracies will be overcome. Today, political parties are increasingly using the internet to interact with members; interest groups use web sites or other digital communications tools; media organizations use new internet supported ways to update the news (Fountain, 2001). Of course, the examples about online information or services offered by government, municipalities or any other organizations may be increased. The bottom line is, the systems stated above (e-government gate, e-pulse, payment through a contactless debit card) or others may be used to make life easier or more practical, as long as citizens can use technology.

Digital technology based or supported functions changes both the habits, actions, production and consumption methods of citizens. Beyond that digital shift changes citizens’ engagement of democracy and equitable participation (Baddeley, 1997; Jordan, 1999; Moore, 1999). As a result, the transformation of every citizen into a good digital citizen is gradually become a necessity. So, the question of what should be the qualifications of a good digital citizen have been discussed in several research. The attempts to identify these qualifications has started a new direction of research on classifications. As a result, digital citizenship qualifications were grouped under nine themes (Figure 5) by Ribble (2009). As it can be seen from figure 5, these qualifications are digital access, digital commerce, digital communication and collaboration, digital etiquette, digital fluency, digital health and welfare, digital law, digital rights and responsibility and digital security and privacy.

Figure 5. Nine Themes of Digital Citizenship (Ribble, 2009)

After Ribble, Education (2012) stated two different policy issues must also be addressed. These are, cloud computing and bring your own devices and digital citizenship policy (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Two different policy issues of Digital Citizenship (Education, 2012)

All these issues should be addressed in digital citizenship education. Shelley et al. (2004) found that attitudes toward technology have also a direct impact on digital citizenry and racial and educational differences affect citizens’ attitudes. So, digital citizenship education programs should include preventive actions to reduce digital divide besides digital literacy skills. However, just having digital literacy skills and positive attitudes are also not enough. Overcoming inappropriate digital communication is as important as teaching digital literacy skills. So, responsible, and component use of technology is the direct focus of digital citizenship education.

REFERENCES

Baddeley, S. (1997). Governmentality. In B. D. Loader (Ed.), The governance of cyberspace (pp. 64-96). New York: Routledge.

Boineau, J. (1998). Fransa’da Devrim Döneminde Yurttaşlar ve Yurttaşlık, Dersimiz: Yurttaşlık, Haz. Turhan Ilgaz, Çev. Yeşim Küey, Kesit Yayıncılık, İstanbul.

Council, E. (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competencies for lifelong learning. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union, 30(12), 2006.

De Coster, I., & Sigalas, E. (2017). Citizenship Education at School in Europe, 2017. Eurydice Brief. Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency, European Commission. Available from EU Bookshop.

Education, A. (2012). Digital Citizenship Policy Development Guide. Edmonton, Canada: Alberta Education School Technology Branch.

European Commission, 2015. Informal meeting of European Union Education Ministers, Paris, Tuesday 17 March 2015. Declaration on Promoting citizenship and the common values of freedom, tolerance and non-discrimination through education. [pdf] Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/educatio n/news/2015/documents/citizenship-education-declaration_en.pdf [Accessed 24 April 2017].

Fountain, J. (2001). Building the virtual state: Information technology and institutional change. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution

Jordan, T. (1999). Cyberpower: The culture and politics of cyberspace and the Internet. New York: Routledge

Kerr, D. (1999). Citizenship education: An international comparison (pp. 1-31). London: Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

Moore, R. K. (1999). Democracy and cyberspace. In B. N. Hague & B. D. Loader (Eds.), Digital democracy: Discourse and decision making in the information age (pp. 39-59). New York: Routledge.

UNESCO (1998) Citizenship Education for the 21st Century.

Shelley, M., Thrane, L., Shulman, S., Lang, E., Beisser, S., Larson, T., & Mutiti, J. (2004). Digital citizenship: Parameters of the digital divide. Social Science Computer Review, 22(2), 256-269.