A global pandemic and its aftermath: The way forward for career guidance

Author: Tristram Hooley, University of Derby

This text is based on a keynote lecture held at the Austrian Euroguidance Conference 2020 "Guidance Matters"

Introduction

I never thought that I would be talking at a conference about public health issues. My research has all been about career guidance and how people pursue their careers and yet here I am discussing the impacts of a global pandemic. I am going to talk about how Covid-19 has changed the way that our careers work, and I'm also going to talk about what we might do in response to that.

Everything about the pandemic is changing every day. We heard about a new vaccine a couple of days ago and so it may be that in six months this is all in the past. [1] I think that probably the recession that is emerging from the pandemic will not be over so quickly. [2] But, we are all struggling to try and understand exactly what is going on and how we can respond to it, and so I hope that these remarks might aid you in your reflections about the future.

What is career?

Career is our journey through life, learning and work. It is our movement from now into the future and so, what we think that the future holds for us individually, and as a society, is central to our careers.

When we understand career as a broad concept, it is not just about paid work. It is also about lifelong learning. It is related to the term ‘bildung’ that you have here in Austria, that we do not really have a translation for in English. The idea that education should be about more fully becoming yourself, about learning about your life and thinking about your role in society. This is where I have tried to situate career in my work, not just as a movement into and through paid work, but as something much broader about how we live our life in the world. And obviously, when we have something like the pandemic that really changes how we act, it also changes our careers.

Career is a powerful concept because it is both life wide and lifelong. By life wide I mean, that we make decisions every day about our lives and how to spend our time. Should we nip away from the Zoom screen and go and make ourselves a coffee or have a chat with our partner? Should we stop working in the evenings and take part in our hobby or see friends or talk to people? These are choices that we are making every day and they are career choices. But career also adds this lifelong dimension. It says yes we are changing things from day to day, but we are also looking across the life course. So if we decide that we are going to leave work early and go and watch the TV and relax that might be a great decision for today, but over our life course it might create a problem if we do that every day. So, career is about making decisions that are both day-to-day decisions about how we spend our time, but also lifelong decisions about how we organise our lives. And of course, there is a strong relationship between those two things because how we spend our days is ultimately how we organise our lives.

Career decisions are not just something that we make once when we decide that we want to be a doctor or a lawyer or a teacher. Career decisions are something that we do every day. Every day we're making career decisions of all kinds. So, career is powerful because it links education with life, and links effort today with outcomes tomorrow. It links schooling and education with society and the economy and it answers the question that young people often ask, which is, why are we learning this, what use will it be? Career is about all of these things and it is about this relationship between our lives, our education and our work. [3]

So what has this got to do with Covid-19?

Over the last few months we have all seen a radical change to our lives. At the start of the year most of us had never even heard of Covid-19. But, by the end of October we were in a situation where there were tens of thousands of cases every day appearing across the world. [4] And so, my life is now really different to how it was before the pandemic.

When you invited me to speak at this conference. I was being invited to come to Austria. And I was thinking, ‘Oh, that'll be great. It will be a really nice trip and I’ll meet lots of people’. A lot of my life before the pandemic was like that, I was going to conferences and seminars and meeting people. But since Covid, my life has become very different. I've lost the ability to travel, to socialise, to go to the gym or the pub.

We have just entered a new phase of lockdown in in the UK.[5] So I'm still working. But I'm now doing it without any direct human contact. I look out of my window and see a brick wall. So, it's very different than if I'd come to Austria. I'm not alone. The pandemic has resulted in a lot of changes in the way our lives have operated for all of us. Many of our working lives and our family lives are very different.

One of the things that we need to recognise is that these changes, and the pandemic as a whole, are not just completely random occurrences. There are many things about the pre-pandemic world that have resulted in the situation that we are in. For the past few decades neoliberalism has characterised the political economies of countries in Europe and, many would argue, across the whole globe.[6] But since the 2008 financial crash this system has been struggling and the current crisis further exposes the flaws in the system.[7]

Even the prevalence of the pandemic itself is influenced by the kind of world that we have built. Pandemic specialist Nita Madhav and her colleagues argue,

pandemics are large-scale outbreaks of infectious disease that can greatly increase morbidity and mortality over a wide geographic area and cause significant economic, social, and political disruption. Evidence suggests that the likelihood of pandemics has increased over the past century because of increased global travel and integration, urbanization, changes in land use, and greater exploitation of the natural environment. These trends likely will continue and will intensify.[8]

way that we organise our society has made it more likely that we will have pandemics and that when we have pandemics they will have a greater impact. We have created a world which is susceptible to pandemic due to environmental destruction, globalisation, unfettered movement of, at least some, people and the rolling back of the state and the loss of public and state capacity to actually manage this.[9] So there are some things that about the way in which our society is organised that have made contributed to the severity of the current crisis.

This realisation forces us to ask both how we are going to organise our societies in response to the pandemic and how, ultimately we might organise them after the pandemic. How are we going to define the new normal, in whose interest will this be organised and what kind of environment will this new normal offer for people to pursue their careers. Some people are enthusiastically cheerleading this change, arguing that it will spell the end for neoliberalism, but so far many of the political experiments that have deviated from neoliberal orthodoxy have been worse rather than better and have maintained a great many continuities with the power-hierarchies of neoliberalism whilst increasing authoritarianism and attacking liberal democratic norms. [10] Of course there are also more hopeful signs with the growth of movements for more equal, more democratic societies, but the future remains unwritten, and the pandemic has so far asked more questions than it has answered. [11]

The new normal is not fixed or inevitable. It is going to emerge in response to circumstance and in response to our actions and decisions. It will be defined by politics and how we collectively decide how to respond. But, it will also be defined by organisations, including employers and learning providers, and by individuals as they negotiate new ways to organise careers and employment. For example, many industries have tried experiments with homeworking that have the potential to change people’s work/life balance. [12] Whether these experiments will endure and reshape the working day beyond the crisis remains to be seen.

The individual and collective responses to the crisis are inter-twined, with each enabling and constraining the other. Ultimately, the future is in our hands. It is up to you and up to your clients and students to define how the world is going to develop from here. Whether it is going to be better or worse is not pre-decided. We have the capacity still to influence that on many levels. Given this, when think about career, we cannot ignore the pandemic as it both shapes the environment in which we conduct our careers and, in turn, our careers will shape how that environment develops.

In this lecture I am going to talk about how the pandemic has become intertwined with our careers. I am going to focus on the economic and labour market impacts of the pandemic and on the psycho-social impacts. I am then going to go on to say something more about why we need career guidance in this situation and explain why this guidance needs to be delivered, at least partially, online and why it needs to be connected to social justice.

The long ascent

The International Labour Organization (ILO) have been publishing regular research on the labour market impacts of Covid-19. [13] It demonstrates that the pandemic has had an enormous impact on people’s everyday working lives. In some countries we have seen extended periods where the labour market has pretty much closed down altogether. Even now, the ILO still estimate that the majority of working people in the world are experiencing some sort of lockdown or special working arrangements to try and combat the pandemic.

These kinds of dramatic changes to global labour markets are slowing the speed of growth of the economy, restructuring which elements of the economy are most profitable and able to employ the greatest number of people. Ultimately these changes open up the possibility of a more fundamental change in the way the economy and the labour market operates. Worryingly many of the changes that we are seeing in the short term, such as the collapse in the retail, travel and hospitality sectors are particularly damaging to young people and to those who earn the least and have the least financial resilience. [14] Of course, the changes are also opening up some new opportunities in other parts of the economy, but overall, in the short to medium term, the impact appears to be a contraction in the number of jobs.

The unique challenges that Covid has posed for occupations which are centred around human interaction is an enormous problem for the labour market. These occupations are often important as entry points to the labour market and employ a lot of people. So, the collapse of these sectors is not just the loss of an industry, but ultimately a change to the whole shape of the labour market. These changes will exert a long-term impact on people’s career prospects.

Gita Gopinath, who is the chief economist at the IMF says,

this crisis will leave scars well into the medium term as labour markets take time to heal, investment is held back by uncertainty and balance sheet problems and lost schooling impares human capital.

All countries are now facing what I would call the Long Ascent – a difficult climb that will be long, uneven, and uncertain. [15]

If someone at the heart of the global financial system like Gita Gopinath is concerned that the global economy is wobbling, I think that we all need to worry. When the pandemic began, we were told that we were going to have a V shaped recession. [16] The lockdown measures would create a rapid fall in the in the economy, but it would quickly recover because the existing economy was essentially being put on ice. But the pandemic has gone on too long, and short-term closures have started to become structural changes. Given this most countries can probably assume that it will take a long while to recover even if the vaccine arrives tomorrow. This radically changes the context within which people are pursuing their careers.

A pedagogic moment

So far, we have described the problems with the labour market and with the economy. We might see these as the external factors that are shaping people’s careers. Now let us turn to how the pandemic is shaping our internal lives. We might think about these as the psycho-social impacts of the pandemic because they are concerned with the relationship between how we think and feel and the outside world, which is currently characterised by twin public health and economic crises.

I have already touched on how my life has been changed by the pandemic and suggested that I am not alone in experiencing these changes. I am spending an awful lot of time in front of a screen. It has made me realise that I pursued my career in the way that I did partly because I did not want to spend all day in an office sitting down and typing. I wanted to be out of the office, teaching, conducting social research and giving talks and lectures. I enjoyed the movement, the variety and the interaction with other people. Now my day to day working experience is very sedentary. Others have experienced different changes to their working life, whether it is a requirement to wear a mask, work in a socially distanced way or change occupation altogether.

These changes to our working routines are profound and so we should expect them to have a radical impact on the way that we think about our lives and our careers. At the heart of this is a fundamental but highly complex shift in our social connections. On one hand we are physically isolated. But on the other hand, the pandemic has really reminded us, how much we need each and how interconnected our societies are. Illness is transmitted through our social connections, and because our societies are so networked the illness moves quickly and spreads across vast distances.

The pandemic has shown how critical our social infrastructure is. If I get ill, I will need somebody to be there to look after me. So, one of the things we've been talking about a lot is the burden placed by Covid on our healthcare systems. [17] We are not just individuals buying healthcare support, rather healthcare is a social system staffed by people and based on a set of assumptions and expectations about what level of support we can expect. If demand surges, supply collapses. The market has limits. This is a societal level problem that require societal level thinking to manage it.

So, we are in a contradictory position where, on one hand we are isolated, but on the other, we are more aware of the social context of our lives than ever before and more dependent on the behaviour of others and the existence of functioning social infrastructure. We cannot ignore how connected we are and how important those connections are.

The pandemic has encouraged us to recognise our fragility and our vulnerability. It has made many of us think about what happens if we get ill. We might have assumed that we were invulnerable, that we would never get ill or lose our jobs before we got to old age, but Covid-19 makes us recognise the possibility of ill health and that the physical and career consequences of illness could be very serious indeed. It has also increased the prevalence of mental health problems both in the education system and in employment and these in turn decrease people’s capacity to manage labour market insecurity and have knock on effects on their physical health. [18]

The psycho-social impacts of the pandemic change the way we perceive our position in the world. They make us think about what is important, they may change the way in which we think about money, wealth and power. For some people they may increase the value that is placed on social interactions, friendship and human connection. In an article that I wrote with Ronald Sultana and Rie Thomsen we argued that the lockdown is a pedagogic moment. It is a time for learning. It is a time for people to think about and rethink their lives and careers. And our role as careers professionals is to help people to do this, but also to help them to recognise that the possibilities that are available to them are framed by the wider social possibilities.

In such a situation our role as careers workers is to help people to see that there are a range of different solutions to this crisis and that we need to think them through carefully and consider who benefits from each of them. [19]

The changes that we are seeing in response to the pandemic shift the possibilities for both individual career change and for social change. New things become possible (or impossible) in our lives, in part because new things become possible (or impossible) for society. The pedagogic moment allows us to rethink our careers and how we want to live our lives, but it also creates political space for rethinking how our societies work including what careers and occupations are valued.

In the UK we have discussed according greater value to those workers who are on the front line whether they are working in the healthcare system or perhaps putting themselves at risk whilst working in retail environments. If someone is sitting there all day, potentially risking their health to provide something that we all need, perhaps we should value that person more. [20] This revaluing of occupations has the potential to change the hierarchies in the labour market and shift how people think about careers. But, for the value of occupations to really change there is a need to do more than celebrate key workers. There is a need for both a social change and a shift in individual career priorities.

Career guidance needs to radically and quickly reform

We are in a period of crisis and change. During periods like this people need more help to find their way around social and economic systems. And that's what career guidance is about.

Career guidance supports individuals and groups to discover more about work, leisure and learning and to consider their place in the world and plan for their futures… Career guidance can take a wide range of forms and draws on diverse theoretical traditions. But at its heart it is a purposeful learning opportunity which supports individuals and groups to consider and reconsider work, leisure and learning in the light of new information and experiences and to take both individual and collective action as a result of this.(p.20) . [21]

This definition reminds us that ultimately career guidance is about helping people to think about their future, but it also reminds us that we can do this in lots of different ways. Because it is about helping people to think about change and transformation it becomes even more important when there is a lot of change and when people need help to generate solutions and ways forward.

Guidance is critical because under the influence of the pandemic work is disappearing, work is changing, work life balance is shifting transitions are becoming more difficult and many, many people are going to have to make career shifts over the next few years. Already people are finding that the occupation that they worked in, the company that they worked for has either changed or disappeared since the pandemic. These people are going to have to figure out how they are going to respond to these changes. Because of this career guidance has to be part of the post-Covid reconstruction strategies that countries develop.

Although it is important to make the argument for career guidance, we also have to recognise that the nature of career guidance is likely to be transformed by the pandemic. In the article that I wrote with Ronald and Rie at the start of the pandemic, we said,

The pandemic served to give the knock-out blow to stable conceptions of the nature of work, leisure, family life, and society. Much of the advice that we might have given about how to build a successful career can simply be cast aside. In a world where going into the office, networking and attending an interview are all things of the past career guidance needs to radically and quickly reform its messages. [22]

It is essential that government should fund career guidance to support the population to move into the post-pandemic future. But, it may be quite a different type of career guidance that is needed as we move forwards. The social distancing approaches have made it clear that career guidance has to be able to be delivered digitally and that careers professionals have to be digitally competent. Digital guidance can no longer be viewed as a specialism or as an option, it has to be core to what we do.

There are other more existential ways in which career guidance is changed by the situation that we find ourselves in. In a period of economic recession we cannot promise that attending to your skills and your career will necessarily lead to you a materially better life. We can help our clients to become more resilient, we can help them to survive and hopefully to move their lives forward. But, but we cannot necessarily guarantee that we can take them back to where their lives were before the pandemic. This highlights the reality that individuals’ prospects for a better life are not solely determined by their career management skills, but rather by the wider political and economic context. Our lives and careers, just as much as our health, is bound up with other people. A new approach to career guidance will recognise this and support and encourage collaboration, co-operation and collective action.

Integrated and digital

Since the pandemic we have seen a lot of change and the way that the guidance is delivered with a great deal of delivery moving online in response to the social distancing requirements. If I had come to talk to you in February, and said that over the next six months, you are going to be able to deliver everything you do online and you are all going to be doing digital guidance all the time, you probably would have said it was not possible, that you needed more training and support and that you were not sure whether online guidance was even a good idea.

The pandemic has fostered an enormous creativity from guidance practitioners. You have figured out how to deliver the important work you do in a whole range of new and different ways and in a rapidly changing context. But it important that we have a theoretical and evidential basis for our work, even when it is innovative and digital. Luckily, over the last few years there has been a lot of work going on in Norway which has helped me to think through what high quality digital guidance might look like.[23] I have been working with my colleague Ingrid Bårdsdatter Bakke to run a course at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences where we have been developing ideas about digital guidance and training Norwegian practitioners to make effective use of its potential.

A lot of our thinking about digital guidance has made the argument that it should be strongly connected to the wide range of other ways in which people access help and support with their careers. Digital tools open up a lot of new possibilities for career guidance which we should be really excited about. The possibility to access and share information, including multi-media information, the opportunity to automate some of the routine process of guidance, to create games and simulations that provide rich learning environments, and the explosion of new forms of communication and interaction. These possibilities should be celebrated and embraced, but we need to remember not to get caught up in the excitement of new tools and forget what they are for. So, rather than talking about ‘digital guidance’ we have proposed the terminology of ‘integrated guidance’ and used this framework to develop approaches to guidance that allow it to be more flexible in situations like lockdowns.

Integrated guidance does not have to be delivered entirely online but it does seek to make better use of online technologies than has often been done in the past. This has become more important in the current situation. My Norwegian colleague and I have developed a few principles that may be useful in guiding the development of integrated guidance during the pandemic and beyond.

The first principle recognises that careering is an active learning process through which people learn about themselves and the world and consider how the two fit together. All forms of career guidance are designed to support individuals in this learning process. Career development has a knowledge base that can be taught, we need to know some things to career effectively. It also takes place in a cultural context which needs to be acknowledged and is fundamentally social in nature. So, while we should digitise guidance, we should not try and fully automate it, nor should we try and offshore it. Ultimately the creative learning relationship between the guidance practitioner and their student or client needs to remain central.

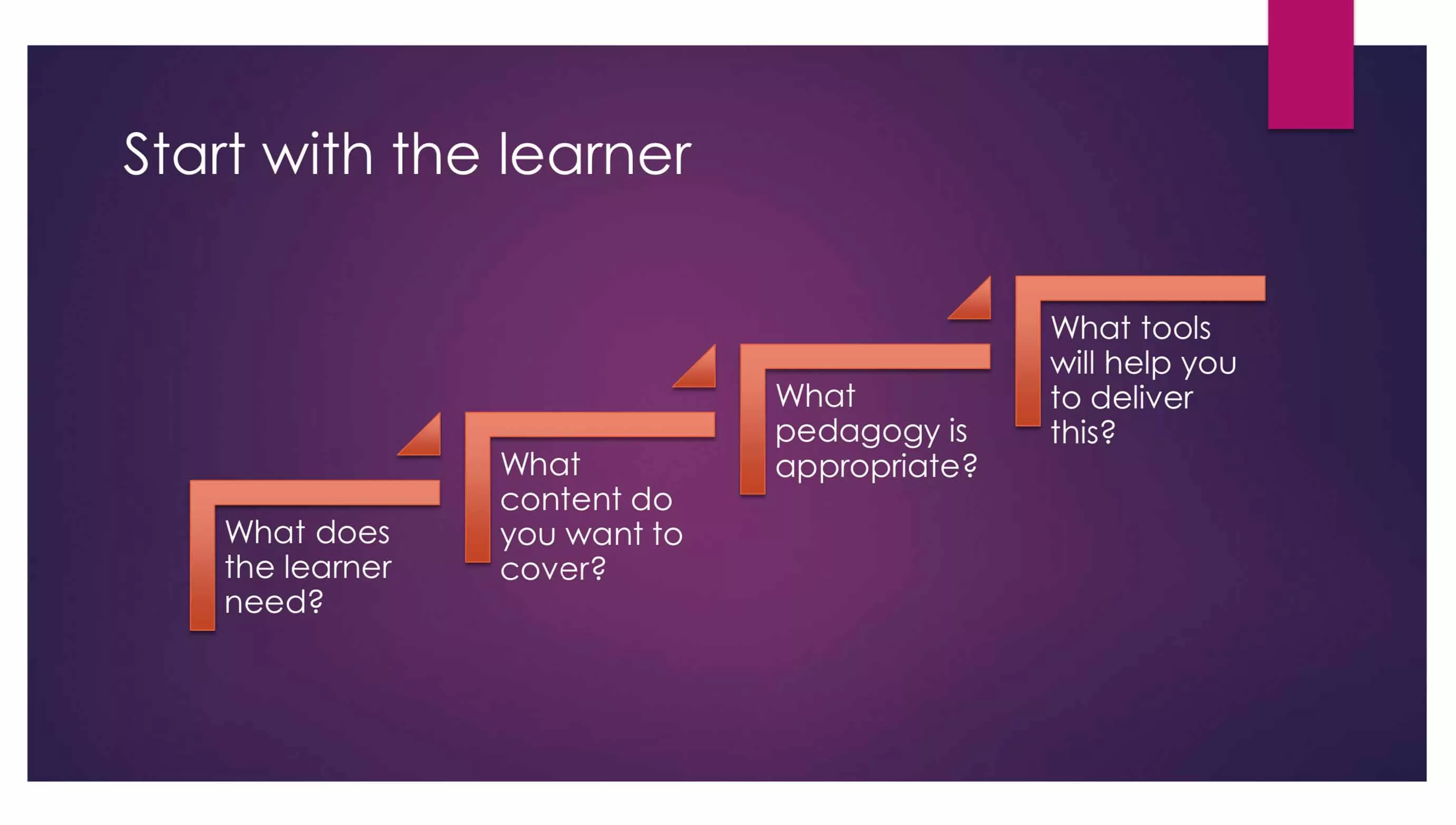

The second principle of integrated guidance is the idea that we should be using an instructional design approach.[24] Instructional design is about thinking about how we deliver learning and guidance to people in the best way. It is summed up by the metaphor of using the right tool for the right job. You do not want to try to bang a nail in with a screwdriver. In the same way you do not want to use lots of technology to deliver guidance, if the client is frightened and confused by it. We do not start with the idea that we should be delivering digital guidance. But, equally we do not start by thinking that we are necessarily delivering face-to-face guidance. Our starting point is thinking about what it is that this student or client needs to learn? What is it they need to engage with? What support do they need? Once we have figured that out, we can then start to consider the best way to deliver guidance to them. Instructional design also reminds us that we need to pay attention to the constraints that we are operating under and obviously the pandemic gives us quite a lot of new constraints. But we approach guidance as a design task, one where we think about what the learner needs, what the constraints are and what possibilities different digital and analogue tools and approaches offer us.

Instructional design is really about remembering to always start with the learner. We should ask what does the learner need? What kind of content will they benefit from? This then leads us, through the application of an instructional design approach to considering what pedagogy is appropriate and how we are going to teach this and what technologies and tools are the right ones to deliver this. For some of our clients that might be a phone call, for others that might be an interaction on WhatsApp and for others it might be a face-to-face meeting.

Our third principle is to adopt a co-careering stance when we are developing and delivering integrated career learning.[25] When we work with people in digital environments we find ourselves in a different sort of relationship than we might have had in a counseling or teaching environment. Digital environments are typically more open and informal. They offer the possibility for more group and community interaction and for more ongoing contact with our clients and students. This is challenging but it also opens up possibilities for new and powerful forms of careers work. Our clients can see us and interact with us over a longer period. We have to learn to relate to them in non-hierarchical ways and to model good behavior. So, if we talk about something like setting up a LinkedIn profile, our clients can go and have a look at our LinkedIn profile. We need to be able to demonstrate effective career management as well as just talk about it.

Signposts to social justice

So far I’ve argued that guidance practitioners need to help people to think beyond their immediate reaction to the crisis and consider how they would like their life, their career and their society to develop over the long-term. This recognises the lifelong perspective that career gives us and uses it as a way to expand the possibilities that are available to people. This is suggestive of a new approach to guidance which is aware of the inequalities that exist in the world and the way in which our careers are embedded into social and political systems. But, if this approach is going to inform guidance practice rather than remain stranded in the realm of theory it needs to offer practical solutions that simultaneously move forward people’s careers and social justice.

With Ronald Sultana and Rie Thomsen, I have developed a framework to support this social justice approach. We describe the framework as the ‘five signposts to socially just career guidance’ because they are designed to provide inspiration and direction.[26] They are not prescriptive, and we hope that other people will add to them. But what the signposts offer us is five ways of doing career guidance that engage with the complex and unequal context in which we find ourselves and which provide ways to help our students and clients to develop their careers, deal with the current crisis and importantly to build their understanding about what is happening and why.

The first signpost is about supporting clients to develop their critical consciousness. This is about helping them to gain a deeper understanding of what is happening in the world and in their career and to develop an analysis about why this is happening. We need to help people to understand politics and environmental issues and to think about what is going on in the labor market. Understanding why does not necessarily solve people’s career problems, but it does place them in a stronger position to develop solutions.

The second signposts says that career guidance practitioners should help people to name oppression. People need to be able to recognise when they are having particular problems because of who they are, rather than because of what they have done. Naming their oppression helps people to correctly allocate responsibility and to see that problems and failures may not be their fault. It also helps people to frame the problems that they face differently and opens up the possibility for a wide range of resolutions to these problems.

The third signpost encourages people to question what is normal. We are in a very strange period when what is normal is not very clear at all. Writing about another global crisis, the philosopher Antonio Gramsci said,

the crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.(p.276) [27]

As people struggle to manage their careers in the current moment, they are assailed with a range of competing ideas about what to expect and what they should desire. Some are the norms of the old world, some might be new norms being born, others will be Gramsci’s ‘morbid symptoms’. As career guidance practitioners we need to help people to analyse these norms and situate themselves in relation to them. Not all norms are bad or oppressive. Society needs norms to function, but norms are socially constructed and contestable and we should try and help our clients to become more aware of the contingency of these norms. We also need to spend time with clients thinking about what a return to normality really means and what the new normal could and should look like.

The fourth signpost points towards other people. It is about encouraging people to work together, to recognise their interconnectedness with others and the power that comes from collaboration, co-operation and collective action. Careers practitioners need to encourage individuals to recognise the power that lies in their social networks and their communities and play a role in facilitating social interaction and collaboration. In the current context this is likely to build on what I have already said about integrated guidance and manifest through the use of digital tools to support the growth and connectedness of communities.

The final signpost argues that careers practitioners need to work at a range of levels. Career guidance should not just be viewed as work with individuals or groups of learners. It has to encompass all of the ways in which we might support people to advance and develop their careers. In many cases this may require interventions into schools and businesses or into wider social and political systems. Career guidance practitioners need to be prepared to be brokers, advocates, agitators and social system designers as well as counsellors and teachers.

What we are trying to do with the five signposts is to give you a practical way that you can take some of these big and abstract ideas about the context in which we live and what the future might hold and respond to them through forms of practice that both help individuals and move us towards a more socially just society. Social theory is important, but it has to recognise the reality of a careers professional sitting face to face with someone, perhaps in a Zoom meeting or in a classroom with a group of people and trying to help them to move their career forwards. The approach that I have outlined here says that this task is easier if we foreground, discuss and ultimately try and change the context in which careers are taking place.

Hope for the future

Covid-19 has posed some big questions for our society, for people trying to build a career and for those careers professionals who are trying to help them. How we answer these questions is going to shape how the future unfolds. I have sought to argue that career guidance has a really important role to play in shaping that future. We are helping people to define the new normal and to find their way to a new kind of life that works for them.

At the start of this lecture I shared a lot of bad news, but, I remain hopeful about the future and I hope that you do as well. The positive psychologist Shane Lopez says that hope is not just about an unjustified belief that everything will work out alright.[28] Hope is about the joining together of optimism (the belief that things can get better) and agency (the belief that you can do something to influence how things turn out).

I think that this kind of hope is exactly what we are trying to foster in careers work. In the social justice approach, we give this positive psychology version of hope a bit of a social and political twist. We are saying to people that they have a role to play in bringing change about in their lives, their communities and their societies. We are trying to help people to see that they have got some capacity to change things in their lives and to make things better and that the world and the future is not fixed. It is better to think ‘how can I make my life better and my world better’ than it is to resign yourself to oppression and disappointment. But hope, requires all of us to act and to act together.

I am also anxious about the future and there is lots to be anxious about. But I remain hopeful because I believe that we have the opportunity to improve the world, and I believe that as career guidance practitioners, we can have a profound effect on the people that we work with. Hopefully in this lecture, I have given you some ideas about how we might try to do that in such a difficult time.

References

Bakke, I.B., Hagaseth Haug, E. and Hooley, T. (2018). Moving from information provision to co-careering: Integrated guidance as a new approach to e-guidance in Norway. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 41(1), 48-55;

Blakely, G. (2020). The Corona crash: How the pandemic will change capitalism. London: Verso.

Boseley, S. & Oltermann, P. (2020). Hopes rise for end of pandemic as Pfizer says vaccine is 90% effective. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/09/covid-19-vaccine-candidate-effective-pfizer-biontech

Brewer, M., Cominetti, N., Henehan, K., McCurdy, C., Sehmi, R. & Slaughter, H. (2020). Jobs, jobs, jobs Evaluating the effects of the current economic crisis on the UK labour market. London: Resolution Foundation.

Cosslett, R. L. (2020). Working from home has offered people a glimpse of how things could be different. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/nov/18/working-from-home-living-coronavirus-remote

Elliot Major, L., Eyles, A., Machin, S. (2020). Generation COVID: Emerging work and education inequalities. London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Gopinath, G. (2020). A long, uneven and uncertain ascent. IMFblog. https://blogs.imf.org/2020/10/13/a-long-uneven-and-uncertain-ascent/

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooley, T., Shepherd, C. and Dodd, V. (2015). Get yourself connected: Conceptualising the role of digital technologies in Norwegian career guidance. Derby: International Centre for Guidance Studies, University of Derby.

Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2018). The neoliberal challenge to career guidance: Mobilising research, policy and practice around social justice. In T.Hooley, R.G. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.) Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp.1-28). London: Routledge.

Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2019). Towards an emancipatory career guidance: What is to be done? In T. Hooley, R.G. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.) Career guidance for emancipation: Reclaiming justice for the multitude (pp.247-257). London: Routledge.

Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2020). Why a social justice informed approach to career guidance matters in the time of coronavirus. Career Guidance for Social Justice. https://careerguidancesocialjustice.wordpress.com/2020/03/23/why-a-social-justice-informed-approach-to-career-guidance-matters-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/

International Labour Organization. (2020). ILO monitor. Covid-19 and the world of work, 6. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_755910.pdf

John Hopkins University (JHU). (2020). COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd402994….

Kettunen, J. (2017). The rise of social media in guidance. EPALE - Electronic Platform for Adult Learning in Europe. https://epale.ec.europa.eu/en/blog/rise-social-media-career-guidance

Kettunen, J., Sampson Jr, J. P., & Vuorinen, R. (2015). Career practitioners' conceptions of competency for social media in career services. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 43(1), 43-56.

Lopez, S.J. (2014). Making hope happen. New York: Atria.

Madhav, N., Oppenheim, B., Gallivan, M., Mulembakani, P., Rubin, E., & Wolfe, N. (2017). Pandemics: Risks, impacts, and mitigation. In D.T. Jamison, H. Gelband, S. Horton et al. (Eds.) Disease control priorities: Improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd edition (pp.315-346). Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ he World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1_ch17

Merrill, M. D., Drake, L., Lacy, M. J., & Pratt, J. (1996). Reclaiming instructional design. Educational Technology, 36(5), 5–7.

Millar, R., Quinn, N., Cameron, J., & Colson, A. (2020). Impacts of lockdown on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. Glasgow: Mental Health Foundation.

Navarro, V. (2020). The consequences of neoliberalism in the current pandemic. International Journal of Health Services. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731420925449

Riofrancos, T. (2020). It’s a tough time for the left. But I’m more optimistic than ever. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/09/opinion/left-politics.html.

Rodeck, D. (2020). Alphabet Soup: Understanding the Shape of a Covid-19 recession. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/covid-19-coronavirus-recession-shape/

Salmon, J. (2020). The £21trillion cost of Covid: IMF warns the pandemic will cause 'lasting damage' to living standards worldwide. This is Money. https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-8836039/IMF-warns-Covid-cause-lasting-damage-living-standards.html

Sampson, J. P., Kettunen, J., & Vuorinen, R. (2020). The role of practitioners in helping persons make effective use of information and communication technology in career interventions. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(1), 191-208.

Tansel, C.B. (2020). States of discipline. Authoritarian neoliberalism and the contested reproduction of capitalist order. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

UK Government. (2020). New national restrictions from 5 November. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/new-national-restrictions-from-5-november

Webber, A. (2020). Firms urged to ‘step up’ mental health support amid pandemic concerns. Personnel Today. https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/firms-must-step-up-mental-health-support-amid-pandemic-concerns/

Williams, Z. (2020). We say we value key workers, but their low pay is systematic, not accidental. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/07/value-key-workers-low-pay

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2020). Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context. Geneva: WHO.

About this text and the author

This is the text of the lecture given by Tristram Hooley to the Austrian Euroguidance Conference in November 2020. Tristram was provided with a verbatim transcript which he amended to create the text presented here.

For more information about Tristram visit his blog at https://adventuresincareerdevelopment.wordpress.com/.

Footnotes

[1] Boseley, S. & Oltermann, P. (2020). Hopes rise for end of pandemic as Pfizer says vaccine is 90% effective. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/09/covid-19-vaccine-candidate-effective-pfizer-biontech

[2] Blakely, G. (2020). The Corona crash: How the pandemic will change capitalism. London: Verso.

[3] If you are interested in career theory have a look at the self-study course on my blog https://adventuresincareerdevelopment.wordpress.com/2020/09/17/introduction-to-career-theory-a-self-study-course/

[4] COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6.

[5] UK Government. (2020). New National Restrictions from 5 November. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/new-national-restrictions-from-5-november

[6] Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[7] Blakely, G. (2020). The Corona crash: How the pandemic will change capitalism. London: Verso.

[8] Madhav, N., Oppenheim, B., Gallivan, M., Mulembakani, P., Rubin, E., & Wolfe, N. (2017). Pandemics: Risks, impacts, and mitigation. In D.T. Jamison, H. Gelband, S. Horton et al. (Eds.) Disease control priorities: Improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd edition (pp.315-346). Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ he World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1_ch17

[9] Navarro, V. (2020). The consequences of neoliberalism in the current pandemic. International Journal of Health Services. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731420925449

[10] Tansel, C.B. (2020). States of discipline. Authoritarian neoliberalism and the contested reproduction of capitalist order. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

[11] Riofrancos, T. (2020). It’s a tough time for the left. But I’m more optimistic than ever. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/09/opinion/left-politics.html.

[12] Cosslett, R. L. (2020). Working from home has offered people a glimpse of how things could be different. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/nov/18/working-from-home-living-coronavirus-remote

[13] International Labour Organization. (2020). ILO monitor. Covid-19 and the world of work, 6. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_755910.pdf

[14] Brewer, M., Cominetti, N., Henehan, K., McCurdy, C., Sehmi, R. & Slaughter, H. (2020). Jobs, jobs, jobs Evaluating the effects of the current economic crisis on the UK labour market. London: Resolution Foundation; Elliot Major, L., Eyles, A., Machin, S. (2020). Generation COVID: Emerging work and education inequalities. London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.

[15] Gopinath, G. (2020). A long, uneven and uncertain ascent. IMFblog. https://blogs.imf.org/2020/10/13/a-long-uneven-and-uncertain-ascent/; Salmon, J. (2020). The £21trillion cost of Covid: IMF warns the pandemic will cause 'lasting damage' to living standards worldwide. This is Money. https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-8836039/IMF-warns-Covid-cause-lasting-damage-living-standards.html

[16] Rodeck, D. (2020). Alphabet Soup: Understanding the Shape of a Covid-19 recession. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/covid-19-coronavirus-recession-shape/

[17] World Health Organisation (WHO). (2020). Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context. Geneva: WHO.

[18] Millar, R., Quinn, N., Cameron, J., & Colson, A. (2020). Impacts of lockdown on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. Glasgow: Mental Health Foundation; Webber, A. (2020). Firms urged to ‘step up’ mental health support amid pandemic concerns. Personnel Today. https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/firms-must-step-up-mental-health-support-amid-pandemic-concerns/.

[19] Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2020). Why a social justice informed approach to career guidance matters in the time of coronavirus. Career Guidance for Social Justice. https://careerguidancesocialjustice.wordpress.com/2020/03/23/why-a-social-justice-informed-approach-to-career-guidance-matters-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/.

[20] Williams, Z. (2020). We say we value key workers, but their low pay is systematic, not accidental. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/07/value-key-workers-low-pay

[21] Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2018). The neoliberal challenge to career guidance: Mobilising research, policy and practice around social justice. In T.Hooley, R.G. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.) Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism (pp.1-28). London: Routledge.

[22] Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2020). Why a social justice informed approach to career guidance matters in the time of coronavirus. Career Guidance for Social Justice. https://careerguidancesocialjustice.wordpress.com/2020/03/23/why-a-social-justice-informed-approach-to-career-guidance-matters-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/.

[23] Bakke, I.B., Hagaseth Haug, E. and Hooley, T. (2018). Moving from information provision to co-careering: Integrated guidance as a new approach to e-guidance in Norway. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 41(1), 48-55; Hooley, T., Shepherd, C. and Dodd, V. (2015). Get yourself connected: Conceptualising the role of digital technologies in Norwegian career guidance. Derby: International Centre for Guidance Studies, University of Derby.

[24] Merrill, M. D., Drake, L., Lacy, M. J., & Pratt, J. (1996). Reclaiming instructional design. Educational Technology, 36(5), 5–7.

[25] Kettunen, J. (2017). The rise of social media in guidance. EPALE - Electronic Platform for Adult Learning in Europe. https://epale.ec.europa.eu/en/blog/rise-social-media-career-guidance; Kettunen, J., Sampson Jr, J. P., & Vuorinen, R. (2015). Career practitioners' conceptions of competency for social media in career services. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 43(1), 43-56; Sampson, J. P., Kettunen, J., & Vuorinen, R. (2020). The role of practitioners in helping persons make effective use of information and communication technology in career interventions. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(1), 191-208.

[26] Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G., & Thomsen, R. (2019). Towards an emancipatory career guidance: What is to be done? In T. Hooley, R.G. Sultana, & R. Thomsen (Eds.) Career guidance for emancipation: Reclaiming justice for the multitude (pp.247-257). London: Routledge.

[27] Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

[28] Lopez, S.J. (2014). Making hope happen. New York: Atria.

All images are taken from the presentation held by Tristram Hooley in November 2020, available at https://bildung.erasmusplus.at/index.php?id=5246